It was 25 years ago today that California voters approved medical marijuana, setting off a nationwide chain of legalization — but hitting hard highs and lows along the way.

For perspective: In the November 5, 1996 election, Californians voted to hike the minimum wage up to five whole dollars an hour. Here in San Francisco, voters elected a fresh new face to the Board of Supervisors named Leland Yee, whose career would take an interesting turn, while famed sex-work activist Margo St. James fell just short of winning a Board of Supervisors seat in that election.

But the most enduring decision California voters made 25 years ago today was to pass Proposition 215, the legalization of medical marijuana. That first-ever state-level medicinal pot approval set off a wave of cannabis legalization across the U.S. that now covers most of the country.

This medical marijuana initiative was born here in San Francisco — in a booth at the Castro’s Cafe Flore, as the brainchild of local celebrity weed dealer Dennis Peron and the infused-brownie folk hero Brownie Mary. “It was Cafe Flore where Dennis Peron and Brownie Mary met and came up with the idea of Prop. 215,” the cafe’s current co-owner Terrance Alan told SF Evergreen.

But the early legal medical marijuana era was a time of homegrown buds and valid letters from a doctor, not the slick, luxe, convenient dispensary scene of today. And even though medical marijuana became “legal,” many dispensaries and providers were raided or arrested over the years while building the $4.4 billion a year California cannabis industry we know today.

1996-2004: Medical Marijuana Was Legal, but Dispensaries Still Weren’t

Above we see a 1996 photo inside the San Francisco Cannabis Buyers Club, the first dispensary ever to operate in the United States. But it was not called a dispensary, and it was 100% illegal, yet it brought cannabis pain relief to a city population with the highest per-capita rate of HIV infection. Peron (far right) and his gang were cast in the media as California kooks, but their Prop. 215 movement had lined up mainstream funding from Democratic megadonor George Soros, Progressive insurance CEO Peter Lewis, and Men’s Wearhouse founder George Zimmer (“I guarantee it”).

They may have been helped by a raid by state police, wherein the club’s clients and employees, many HIV-positive and visibly sick, were arrested and handcuffed.

“It just did not look good to drag dying people to jail,” says Alia Volz, author of Home Baked: My Mom, Marijuana, and the Stoning of San Francisco, whose mother’s pot brownies were sold at the club. “It was embarrassing to arrest these incredibly sick and frail people. In that huge raid, the California Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement rather thoughtlessly played right into that.”

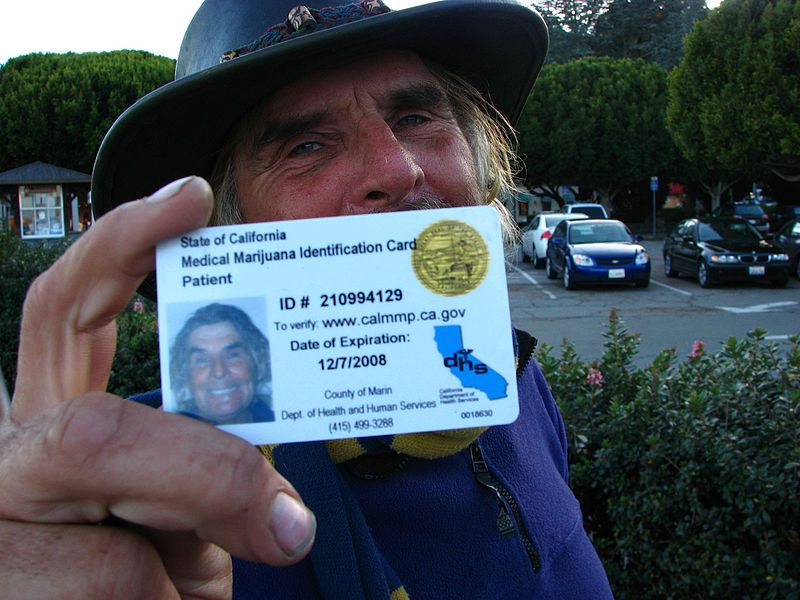

To the dismay of those narcs, Prop. 215 would pass by a 56%-44% margin. Not everyone could get medical marijuana, the text of the law allowed it for people suffering from “cancer, anorexia, AIDS, chronic pain, spasticity, glaucoma, arthritis, or migraine” conditions, and one needed a valid doctor’s recommendation.

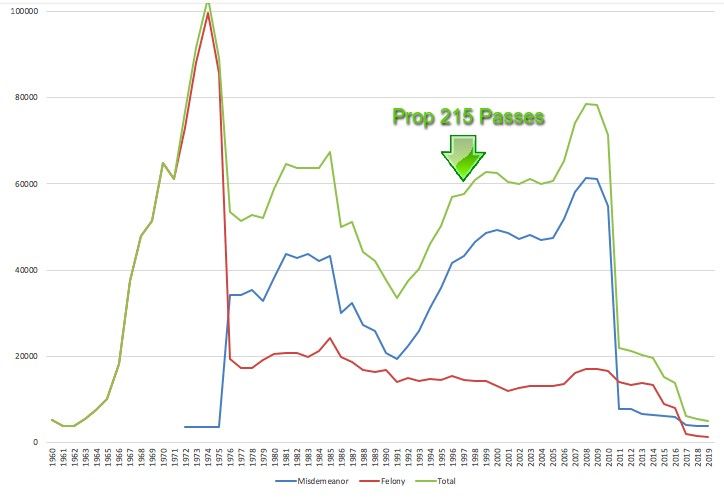

California cannabis arrests actually increased in the year after Prop. 215 passed, as they did the next year, and the year after that, and every year up until 2008. And the cannabis clubs in town were still harassed and raided by state and federal agents every bit as much as they were before Prop. 215. The first club SF club was raided just five months after Prop 215 passed (Flower Therapy on 17th Street), and the hits kept coming.

“My mom tended to steer clear of [the club] and interact with Dennis in other private spaces, in parking lots or on rooftops,” Volz tells SFist. “Dennis was always too hot. He got busted dozens of times, and he wasn’t shy about it.”

President Bill Clinton’s “Drug Czar” (remember when that was, like, an official White House position?) warned he would prosecute doctors who recommended medical marijuana. That, and the ongoing raids, had a pretty chilling effect on the first several years of medical cannabis in California.

2004-2010: Dispensaries Legalized, But Still Get Raided All the Time

It took state lawmakers another seven years to hash out the old Medical Marijuana Card system, through a piece of legislation called SB 420 (heh.) This also allowed for the first real legalization of cannabis dispensaries, and the first generation of enduring dispensaries, like the Green Room, Releaf, and the Vapor Room began to bud.

"I was personally arrested for medical cannabis," Green Cross dispensary founder Kevin Reed tells SFist. "As you can imagine, these arrests, along with the passage of SB 420, had a lasting impact on me and ultimately led me to founding The Green Cross. We first opened The Green Cross at our original Noe Valley location in 2004." (It's now at Mission Street near Silver Avenue.)

“That period was really wonderful, we had lots of dispensaries,” says David Goldman, California NORML board member and SF chapter president of the Brownie Mary Democratic Club. “Most dispensaries were actually collectives.”

This also sprang a network of “pot docs” and “card factories,” wherein perfectly healthy folks would pay their $40 or $50 and claim a medical marijuana recommendation for any old mundane condition like insomnia, anxiety, or even snoring. Dispensaries took on the collective and co-op models as a sort of legal maneuver to increase the number of plants and the amount of bud they could legally have on the premises.

“We had the collective model,” Goldman tells SFist. “People would join collectives and in exchange would get cannabis either at low prices or for free. For every collective member, ten plants were allowed to be grown in most jurisdictions in California. And that allowed collectives to have a lot of members, and grow a lot of cannabis, and take care of their members beautifully.”

In this kind of Wild West era, the whole idea of a ‘retail cannabis permit’ did not yet exist. “If you found a willing landlord, you were set to go,” Vapor Room owner Martin Olive told SF Weekly.

That ended up being the weak link. U.S. Attorney Melinda Haag orchestrated a huge crackdown on Bay Area dispensaries starting in 2011. “They sent letters to the landlord saying, either you close your dispensary or you risk losing your property and going to jail for 40 years,” Goldman remembers. “And a lot of dispensaries just folded after that, we lost a lot of them in San Francisco.

When the old Haight Street location of the Vapor Room closed in 2012, SF Weekly noted that another Ninth Street dispensary, HopeNet, was forced to close the exact same day. “The two closures tonight will mark the seventh and eighth local pot clubs shut down by U.S. Attorney Melinda Haag in less than a year,” the paper wrote.

2010-2015: California Fails to Legalize, and Other States Rush Ahead of Us

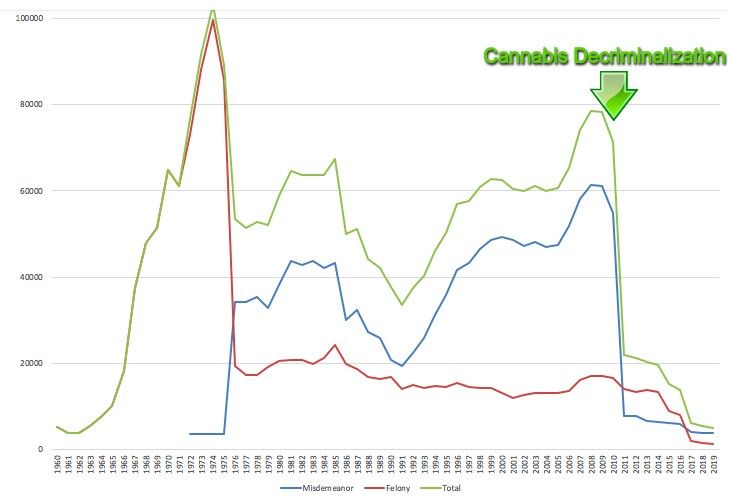

In hopes of changing this, California cannabis activists tried to pass an adult-use, no medical-card-required, recreational cannabis law in 2010, during the Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger era. But this Prop. 19 measure would fail by a 53%-47% margin. “Schwarzennegger signed rather than vetoed a decrim[inalization] bill to take the wind out of the sails of our arguments,” Goldman says. “That left many people voting against Prop. 19.”

Meanwhile, both Colorado and Washington approved recreational marijuana initiatives on the same day in 2012, stripping California of its rightful title as cannabis capital of the country.

Yet Schwarzenneger’s decriminalization bill, which made possession of less than an ounce an infraction rather than a misdemeanor, did lead to a historic drop in cannabis arrests. He is still not remembered fondly by cannabis activists.

“Schwarzenneger has a terrible record on cannabis,” Goldman points out, noting that the governor allowed for medical marijuana users to be fired for using cannabis outside the workplace.

But the green tide was still turning. When rapper Snoop Dogg was part of a $10 million investment in the delivery service Eaze in 2010, it was clear that weed was becoming mainstream, and the legal cannabis cake was just about baked.

2016-2021: Recreational Cannabis Brings on the Green Rush

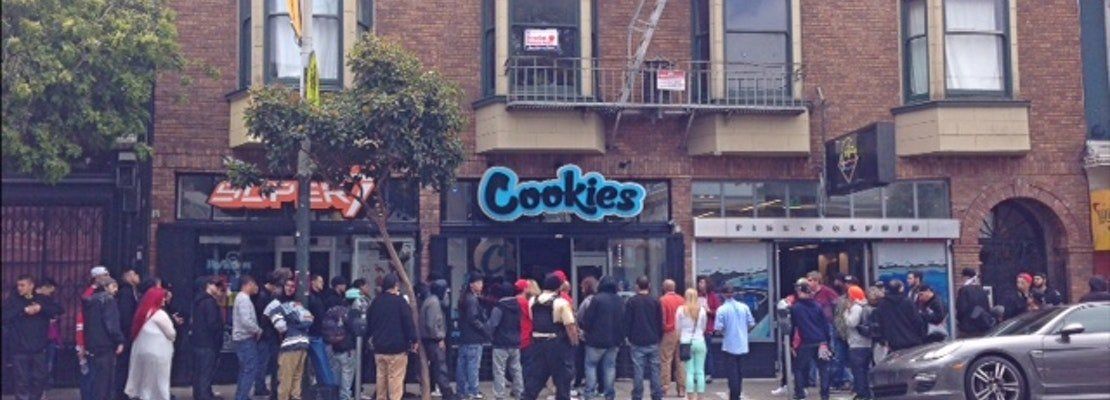

California finally passed the adult-use cannabis law Prop. 64 in 2016, you could legally grow and smoke your weed without a card right away. But you could not yet walk into a cannabis dispensary without that card.

It took state and local lawmakers more than a year to figure out how to implement, regulate, and tax an elaborate new system of retail shops, cultivation rules, and childproof packaging regulations. Cannabis did not become fully legal in California until the morning of January 1, 2018. Here in San Francisco, legal weed sales didn’t start until January 6.

It was like the Dot-Com Boom all over again for cannabis companies, as Bay Area weed brands were suddenly being acquired for tens of millions of dollars. Yet this was smoke and mirrors, as many of these deals were based on funny money and fell apart. And the new legal framework was weeding out small farmers, sole proprietors, and people of color. The new regulations still benefit big companies with institutional investors, who can afford to operate at a loss.

“From a consumer perspective, it has been overwhelmingly positive,” Volz tells SFist. But she points out how the small Mendocino farmers, Black-owned retailers, and Dolores Park truffle guys of the world cannot get established in this framework.

“It heavily favors major investors, it heavily favors venture capitalism, and it’s nearly impossible for small farmers,” she says. “It's put most of the old-timers, both farmers and dealers out of business. And these are people who operated at great risk.”

There is a temptation to say California blew it on this grand legal cannabis experiment, giving the pot of gold to the investor class who did little to build this industry. This may be true. But the legal cannabis trade is filling empty San Francisco storefronts, and providing nearly 60,000 Californians with full-time jobs that do not carry the risk of getting arrested, like those jobs did in the so-called good old days.

“It was the good old days, as long as you didn’t get busted,” says Omar Figueroa, a cannabis attorney for more than 20 years.

In the early years, Figueroa was a criminal attorney trying to keep people out of prison for their involvement in the cannabis industry. Now he’s giving them legal advice on permitting, regulatory compliance, and intellectual property, showing that this legal marijuana in California has grown to maturity.

“Before I was helping people avoid their cannabis nightmares,” Figueroa tells SFist. “Now I’m helping them achieve their cannabis dreams.”

Related: A Brief History Of How 4:20 Became 4/20, Right Here In The Bay Area [SFist]

Top Image: Dennis Peron is a Prop. 215 activist for the legalization of medicinal marijuana and the founder and owner of the Cannabis Buyers' Club in San Francisco. (Photo by Axel Koester/Corbis via Getty Images)