We in San Francisco all are vaguely aware that not everyone who owns a house or condo in SF actually lives here full time, or even part time. But did you know that there are actually tens of thousands of housing units, rentals included, that are sitting empty on any given day for one of a variety of reasons, and that putting even a fraction of these into service as supportive housing could solve the homeless problem overnight?

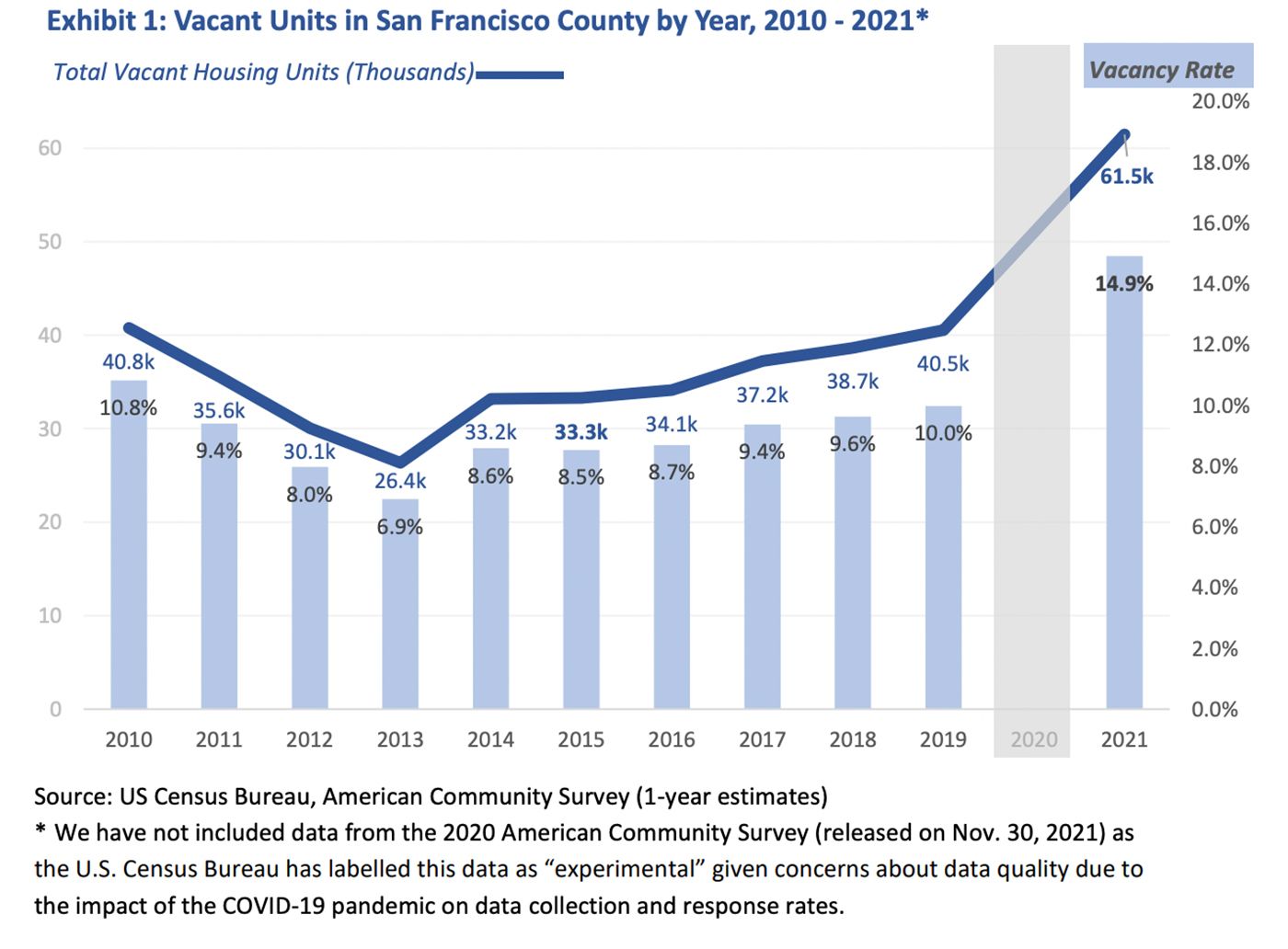

We have an update this week to a previously issued report by the Office of the Budget and Legislative Analyst (BLA), requested by Supervisor Dean Preston, that through readily available Census Bureau data shows that the number of vacant units in the city rose a whopping 52% between 2019 and 2021 — from 40,548 to 61,473.

In that same period of time, SF added 5,870 new units to its housing stock.

As seen in the chart above, the low-water mark for vacant units came in 2013, when the city had an estimated 26,400 units vacant. That number has risen in the years since, but never as sharply as it did during the first two years of the pandemic.

It should bear repeating here that San Francisco lost a significant bit of population through out-migration of primarily younger adults during that first year of the pandemic, between July 2020 and July 2021, as we earlier learned. There's evidence to suggest that a good percentage of people have returned over the course of late 2021 and through 2022, so these numbers may already be outdate. But 61,500 units is a whole lot of living space that was sitting empty while thousands are sleeping on the streets.

The reasons for all this vacancy are numerous, but they fall into a few basic categories: units that are on the rental or for-sale market that haven't rented/sold; units that are being kept off the market because they're being repaired or because their owners just want them to sit empty; and units that technically have occupants, either renters or owners, but those people just are mostly never there because they have some other residence.

The category of "Other Vacant" in the chart above has doubled since 2015, according to the BLA — and this category includes "units held vacant for personal or family reasons, units requiring or undergoing repair, corporate housing, units held for use by a caretaker or janitor, units subject to legal proceedings, units being kept vacant for a future sale, and other reasons," the BLA says.

There were around 7,750 people without permanent homes in San Francisco as of the most recent point-in-time count, around 4,000 of whom are considered unsheltered on any given night.

Using that estimate, Supervisor Dean Preston responded to the report on KRON4, saying, "It is devastating to realize that for every person sleeping on the streets tonight, there are 14 vacant homes in our city."

Obviously, all landlords and building owners with empty units can't be expected to provide free shelter to the homeless, but the contrast is nonetheless striking. And Preston is using this data to try to drum up support for the ballot prop he sponsored, Prop M, dubbed the Empty Homes Tax.

"In a city where the cost of housing is out of reach for most working people, and with thousands of homeless people living on our streets, it is immoral and inhumane to have tens of thousands of homes sitting empty," Preston said in his statement to KRON4. "The dramatic increase in just two years shows the dire need for policy intervention to turn these empty units into places where people can live."

A debate like this is going on in New York City as well, where by one recent estimate there are 60,000 rent-stabilized (comparable to SF's "rent-controlled") units being held off the market — or "held ransom" — by landlords.

The BLA suggests that this is a significant problem that should support activists' arguments about whether all housing is good because it adds to supply, or whether affordable housing has to be prioritized to reach the residents who really need it.

"While new housing supply can be a primary contributor to affordability, particularly if targeted and priced for low and moderate income households, large numbers of vacant units in cities with existing housing shortages can also impact affordability by further restricting supply," the BLA writes. "While a certain level of vacancy can be expected due to normal turnover of housing units, some units may be vacant due to owner preferences and actions that are inconsistent with policy goals of maximizing the City’s housing stock for residents."

Preston made this argument back in February, after an earlier BLA report suggested that 10% of the city's housing stock, or around 40,000 units, was sitting empty. That was Preston proposed a "Empty Homes Tax" for the November ballot, which levies a tax on landlords or building owners with three or more vacant units that sit empty for six months or longer. Starting in 2024, the tax would range from $2,500 to $5,000 per vacant unit, and could rise to a max of $20,000 if the same owner keeps the units empty.

Opponents of Prop M, whose arguments you can find in your voter pamphlet, question these vacancy numbers, and suggest this new tax is just an unfair burden on small property owners.

Calling the Census Bureau's numbers "trumped-up, overstated statistics," the San Francisco Apartment Association writes, "Prop M is a feeble, misguided attempt at housing policy from the Board of Supervisors who refuses to take our housing crisis seriously. This anti-housing Board is creating a problem that doesn't exis in order to raise more taxes on San Franciscans."

Proponents suggest that the numbers are very real, and that a similar tax on vacant homes in Vancouver resulted in a 10% reduction in vacancy.

Previously: An ‘Empty Homes Tax’ Could Be Coming to Your November Ballot

Top image: Kelly Sikkema