Most of us have already absorbed the idea that the coronavirus does some weird and sinister things to the human body that are unlike most other respiratory viruses known to man. But now a new study finds yet another unsettling thing that the virus appears to do to help spread from cell to cell.

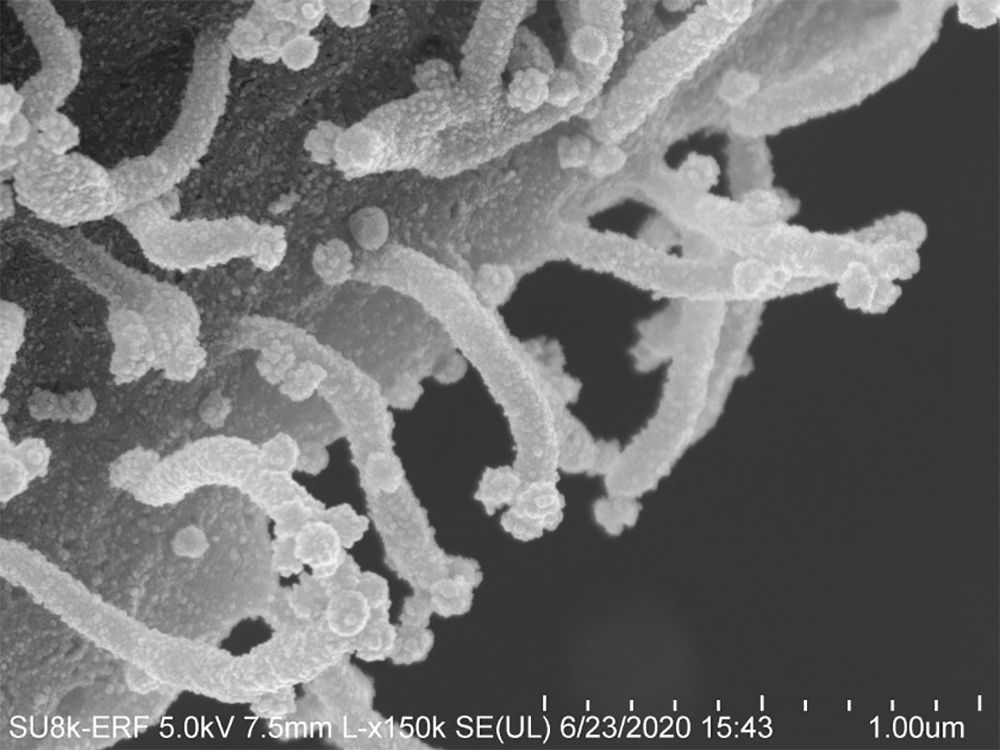

A new study by an international team led by UC San Francisco finds that cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 quickly begin to grow new arms or dendrites — referred to clinically as filopodia — which are themselves studded with fresh virus particles. These filopodia then seek to reach into and through the walls of neighboring cells, thereby infecting them. And this appears to be a second mode that the virus has for replicating and spreading itself in the body.

As the LA Times reports via the study, up until now, researchers believed that this virus spread itself like most other viruses, by docking itself onto healthy cells, invading, and then turning those cells into copying machines. A team in UCSF's Quantitative Biosciences Institute led by systems biologist Nevan Krogan launched a project in February to rapidly identify existing drugs and compounds that might treat or slow the spread of the coronavirus. They published initial findings in late April pointing to 10 existing drugs and experimental compounds that showed promise in lab settings when it came to targeting the human proteins this virus most needs to survive.

The latest study is an extension of that work, and Krogan is one of the lead authors of the paper published today in the journal Nature. The important new finding, Krogan and the team hope, will lead to some rapid study of several existing cancer treatments that themselves inhibit the growth of filopedia — thereby shutting down this second means that the virus is using to invade cells.

"It’s just so sinister that the virus uses other mechanisms to infect other cells before it kills the cell,” Krogan says, speaking to the LA Times.

Krogan says that while other viruses — including HIV and the family of viruses that cause smallpox — also use filopedia as mechanisms of spreading infection, the way this virus so rapidly prompts the growth of these tentacles is highly unusual. And the shape of them, branching off the cell and each other like trees, is also apparently strange. Other infectious diseases like HIV don't cause these kinds of prolific, mutant growths.

Expanding the earlier list of promising drugs, the latest study points to seven cancer drugs already in use that could prove effective against COVID-19. Those include a drug already being used to treat acute myeloid leukemia called Xospata (generic name: gilteritinib); the experimental drug Silmitasertib, which is being studied as a treatment for bile duct cancer and one form of childhood brain cancer; and ralimetinib, another cancer drug which was developed by Eli Lilly to treat multiple forms of cancer.

These drugs are all known as kinase inhibitors, which the Gilead treatment remdesivir is as well.

"We've tested a number of these kinase inhibitors and some are better than remdesivir," Krogan says, via the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel.

Another experimental drug called Dinaciclib was found by the research team to stop the virus's assault on a family of kinases called CDKs, which are responsible for cell growth and dealing with DNA damage.

Other infectious disease researchers are just waking up to the revelations of the paper, but most reactions seem fairly excited. While much research is being done on shutting down virus proteins, Krogan's field of study, called proteomics, instead focuses on the less-likely-to-mutate human proteins involved in helping the virus do its dirty work.

"This paper shows just how completely the virus is able to rewire all of the signals going on inside the cell," says University of Wisconsin-Madison medical professor Andrew Mehle to the Journal-Sentinel. "That's really remarkable and it's something that occurs very rapidly (as soon as two hours after cells are infected)."

And Lynne Cassimeris, a professor of biological sciences at Lehigh University, calls the latest findings "an amazing leap." "We know that the virus has to be manipulating these human proteins," Cassimeris says. "Now we have a list of what is changing over time."

While Krogan's lab at UCSF got this research off the ground just as the pandemic was emerging in February, there were 70 authors listed on the latest paper, with Krogan as the lead. The work was also done by scientists at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York, Rocky Mountain Labs in Montana, the Pasteur Institute in Paris, and the University of Freiburg in Germany