Homeless and addiction-treatment advocates will be the first to tell you that the underlying issues around addiction and the dearth of mental health services that can lead to homelessness are state and national problems, not local ones. But the state of California is putting the onus on cities to now set up CARE Courts in order to divert some of the most severely mentally ill into treatment and away from jail.

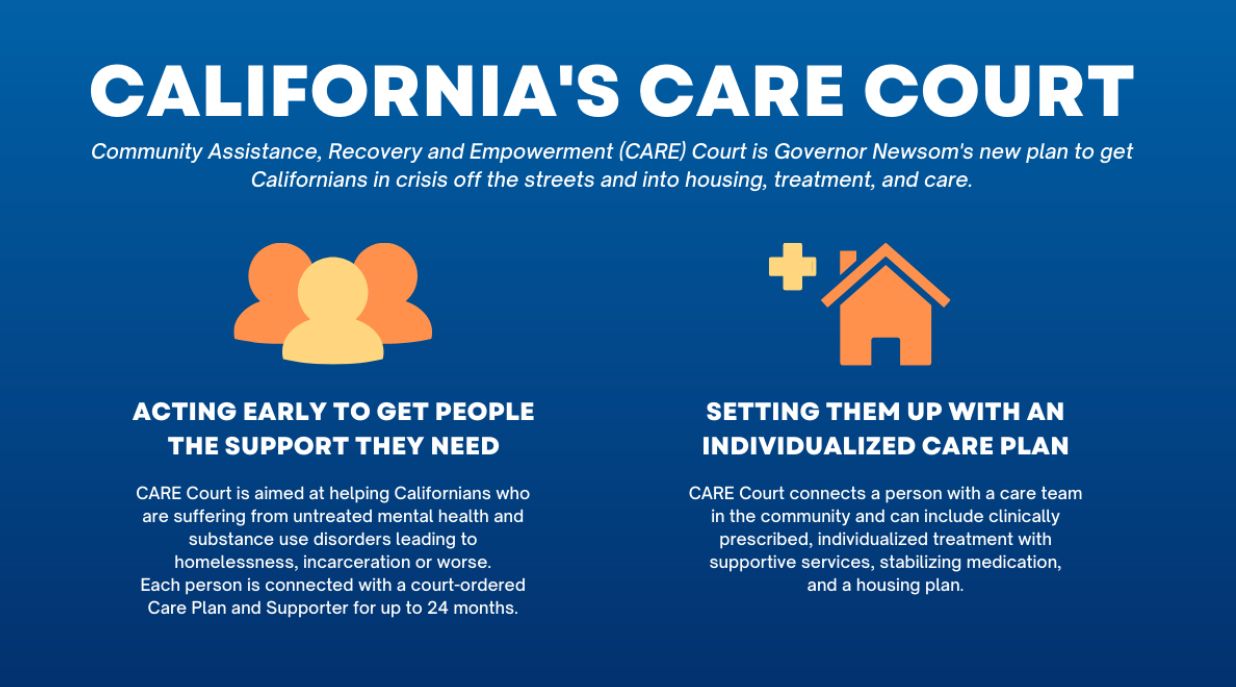

The court focuses on those with schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders who lack the ability to make medical decisions for themselves, and who often also have substance abuse problems. Newsom first proposed the idea of CARE Court — short for Community Assistance, Recovery, and Empowerment — in early 2022, and the legislature made it law last summer.

San Francisco County is among a handful of counties that are obligated under the law to launch the CARE Court system early, starting October 1, 2023. The others complying early are Glenn, Orange, Riverside, San Diego, Stanislaus, and Tuolumne counties. The rest of the state has until December 2024.

But among those counties, San Francisco arguably has the most concentrated problem with chronically homeless and mentally ill people who are already a drain on public resources. The Chronicle reported last summer on five chronically mentally ill people who alone cost the city $4 million in ambulance rides over the course of five years.

And it may come to pass that San Francisco won't be so successful in getting its CARE Court up and running unless the state recognizes that our caseload will be significant, and will require both new housing beds and significantly more city staff hours, which are not part of the budget.

So far, the state has given SF $4.3 million to set up its CARE Court, but Department of Public Health estimates it will cost $50 million per year to keep it running, as the SF Standard reported in April.

Charlie Berman, a social worker who works with the mentally ill in San Francisco, tells KQED this week, "I think CARE Court really isn't going to do much of anything." And Berman notes that existing programs and structures in place in the city to adress mental illness aren't adequately able to do their jobs because of "lack of capacity."

Mayor London Breed has touted the fact that the city has added 400 new beds for mental health treatment in the last three years, but it's unclear where all those beds are — and some are, vaguely, in "neighborhood-based psychiatric respite facilities."

"We're giving people an opportunity, but if things continue to persist, we need to take action," Breed tells KQED, in more of the tough talk she's been using to address the fentanyl crisis and unchecked drug dealing. "The conversation is I'm sure going to turn ugly politically, but it is necessary. People are sick and tired, and we have to clean up the streets."

Supervisor Hillary Ronen tells KQED this week that while she doesn't object to the idea of the CARE Court, she says that city leaders' "inability to stick with one strategy and see it through" is the larger problem when it comes to mental illness.

City Attorney David Chiu notes that the state, while commanding SF to set up its CARE Court by October 1, hasn't allocated any additional funds to cover the extra work that will be involved in them — from city attorneys' offices, public defenders, and other advocates making the court system operate. And Chiu is also concerned about the requirement, under the CARE Court rules, for five hearings before an individual's treatment plan can be approved.

Mayor Breed dismisses concerns about funding, telling KQED, "There's never enough money for anything, period. But the fact is, that can't be an excuse for not trying."

Those who land in CARE Court may be subject to a 12-month treatment plan, which can then be extended for another 12 months, and that may include medication, multiple services, and counseling. Individuals going before a judge will have both a public defender and a designated "supporter" advocating for them, and the state calls this a "client-centered approach."

The consequences for not complying with a CARE Court-mandated plan include conservatorship — though courts have been historically reluctant to force treatment on the unwilling. And participation in the system — which would be an alternative to jail — is voluntary, with the hope being that there is a "black robe effect" of a judge handing down a treatment "sentence" that will funnel more of the severely mentally ill onto more stable paths.

The system also pledges to provide Medi-Cal support for providing "behavioral health services to people struggling the most."

Previously: Newsom’s CARE Court Deadline Looms October 1, But SF Lacks the Beds And Staff to Enforce It

Photo: Tyler Ortiz