One faction of the Recall Chesa Boudin movement bought roughly $2,000 in ads on Nextdoor, but the neighborhood-centric social network removed the ads and returned the payments.

Campaign finance is my kink, so come election time, I am often cruising the back pages of the California Fair Political Practices Commission Form 460 documents posted at the San Francisco Ethics Commission’s website. And in the current California recall mania era, it is always election time.

This week’s cruising brought something I hadn’t seen before — payments to the nosey-neighbor complaint aggregator website Nextdoor. Clearly labeled as “advertising” payments, these were purchased by the original Recall Chesa Boudin campaign that started in March of this year, not the rival faction known as Safer SF Without Boudin that was established the following month and purports to be a more Democratic party-led effort.

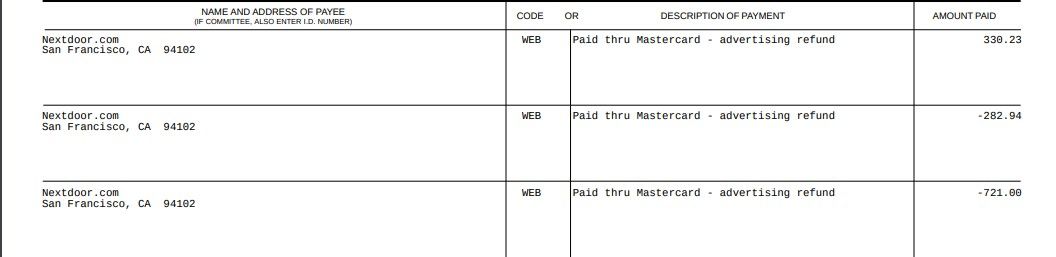

The Recall Chesa ads from the first group, led by former Republican mayoral candidate Richie Greenberg, were five Nextdoor ads totaling just under $2,000, according to the latest campaign finance filings. But while the Nextdoor platform initially accepted the ads, they were quickly removed after displaying for “three or four hours,” or maybe a little longer, as Greenberg tells SFist. Campaign filings show the payments for the ads were almost immediately reimbursed to the recall campaign.

That’s because Nextdoor does not allow political advertising, a position they reiterated before the 2020 election. A Nextdoor spokespeson tells SFist "all of these advertising charges were cancelled and the ads are not live." In previous announcements, the company said “The mission of Nextdoor is to empower neighborhoods to build stronger local communities and we will accomplish that by creating trusted connections between neighbors. We’ve taken a stringent approach to political ads and have banned them from the platform.”

In the big picture, a $2,000 political ad buy is pretty meaningless in a market like San Francisco. (Remember that Juul threw around $11.6 million in their unsuccessful 2019 effort to beat a vaping ban.) So two grand is small potatoes. But the bigger takeaway may be that online platforms are still figuring out how to handle political ads. The old model was to just not allow ads during election season. But when all manner of recall efforts are underway in perpetuity, election season ad policies may end up being permanent ad policies.

Note: This post has been udpated with comment from Nextdoor.

Related: Washington Post Calls Out ‘Inaccurate’ Reporting by Chesa Boudin’s Local Media Critics [SFist]

Images: (Left: SF District Attorney; Right: Screen Gems Television)