A recently released study by researchers in China, examining an outbreak of COVID-19 that occurred among some related and unrelated diners in a restaurant in Guangzhou in January, suggests that air conditioning in an enclosed space can help spread the coronavirus — but not to everyone in a room.

The field study, the first of its kind in this pandemic, was conducted by the Guangzhou Yuexiu District Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and is set to be published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in July. It describes how lunch guests on an entire floor of a five-story restaurant were all quarantined for 14 days after one restaurant patron and several family members became sick. The study has thus been able to assert with some degree of certainty that the infection in one family was able to spread to people dining at two adjacent tables in the restaurant, likely due to airflow, but not to 73 other people who were eating in the same room that day, or to any of the eight servers working that floor.

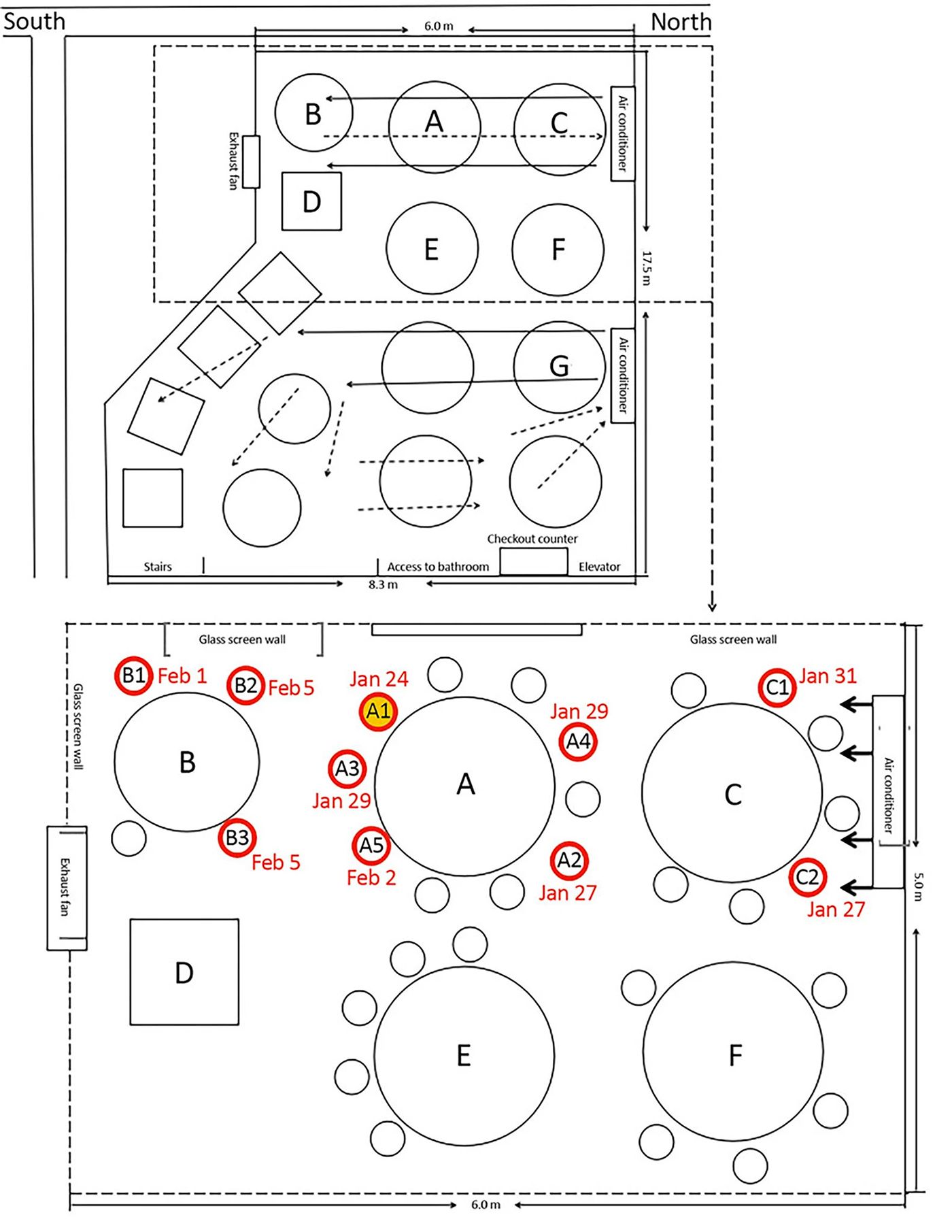

The diagram below shows the table at one side of the dining room where Family A, as they are called in the paper, were eating on January 24. Family A had recently left Wuhan, which is 520 miles to the north of Guangzhou, and no one was showing any symptoms of illness when they sat down to lunch. Later that day, however, a 63-year-old woman in the family — identified as A1 in the diagram — came down with a fever and a cough and was taken to a hospital where she tested positive for the virus. Within several days, by January 29, two other family members became ill, and by February 2, an additional two had tested positive.

Also in that same timeframe, two people eating at Table C contracted the virus, and by February 5, three people at Table B had as well. The diagram shows how an air conditioning unit next to Table C likely blew air — and the virus — across Table A and onto Table B, and likely bounced off the walls back to Table C.

The upper diagram shows how airflow was emanating from a different AC unit across the other part of the dining room, where no one became ill.

"We conclude that in this outbreak, droplet transmission was prompted by air-conditioned ventilation," the authors write. "The key factor for infection was the direction of the airflow."

As the New York Times suggests, this study "illustrates some of the challenges that restaurants will face when they try to reopen." Concerns about airflow, spacing of tables, and screening for infected patrons are likely going to be major factors in making the public comfortable to dine out again.

The study also confirms what the CDC has acknowledged in recent weeks, namely that airborne spread of the virus is possible without coughs or sneezes, and just from talking or exhaling — though we can not be certain that anyone in Family A did not sneeze or cough once at this meal.

It's also not certain whether the first patient in this study, the 63-year-old woman who was the first to show symptoms, was in fact the first person infected in her family — one or several of the other four family members could have been asymptomatic spreaders at the time of the lunch.

And the hopeful detail to come out of this study is that tiny, aerosolized particles were not likely hanging in the air of this dining room for a lengthy period, since the servers and the 73 other restaurant patrons, all of whom were later tested, were not infected.

But the fact that unrelated people at nearby tables were infected is a cause for concern as restaurants and other businesses where people linger for extended periods, like gyms, are going to feel like potential hazards until this pandemic fully recedes, or until a vaccine is made and widely distributed.

"To prevent the spread of the virus in restaurants, we recommend increasing the distance between tables and improving ventilation," the researchers write.

But, psychologically, will that be enough?

Harvey V. Fineberg, head of the Standing Committee on Emerging Infectious Diseases and 21st Century Health Threats at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, tells the Times that the study is "illuminating for the kind of thing we need to keep learning about as we try to configure safe work spaces." And he suggests that germicidal ultraviolet lights may be something that restaurants, bars, and other workplaces will need to consider.

Another consideration may be a newly developed device out of Switzerland that purportedly can detect the novel coronavirus in the air — though that could lead to panicked stampeding when it goes off.

This study will at least set at ease those like myself who have been made nervous by the anecdotal case of the choir in Washington State where potentially a single infected person spread the virus to 44 out 60 other people in an enclosed room in March. Singing may be a better spreader than talking over a meal, this should tell us, and also as an infectious disease expert said of that case, certain people are simply super-spreaders when it comes to the capacity of their lungs to expel tiny particles — some capable of exhaling 1,000 times more fine material than the average person.

Related: Super-Spreading Event In Washington Suggests Coronavirus Is Airborne Without Coughs or Sneezes