The new Monet exhibit at the deYoung Museum in Golden Gate Park has been a major draw since debuting two weeks ago. I checked it out in the middle of a crowded Sunday, and I have some advice.

There are also a few things you should know about "Monet: The Late Years" before going, because it's not exactly what you may be expecting. As the museum explains in this excellent primer, which you may want to read before going, the show focuses on the last decade of Monet's life, when his eyesight was quickly degenerating due to untreated cataracts.

At one time hailed by a director of New York's Museum of Modern Art as "the grandfather of Abstract Expressionism," Claude Monet's legacy is still being defined in many ways — and this exhibition, bringing together a collection of late works not often seen side-by-side, is a part of that ongoing conversation.

Some recommendations and takeaways:

1. You may want to avoid weekend days, but if you have to go then, reserve a scheduled time slot ahead.

If you don't do this, you may end up annoyed or disappointed, with a long delay before you're allowed in and without enough time to enjoy it. Monet being Monet, the place was mobbed this past Sunday, and the earliest I was allowed in with a friend's member pass was 2 hours after we arrived. Also, if you're not a member, be prepared to pay $35 to get in to the Monet show.

2. There is only one room of what you'd call typical Monet works

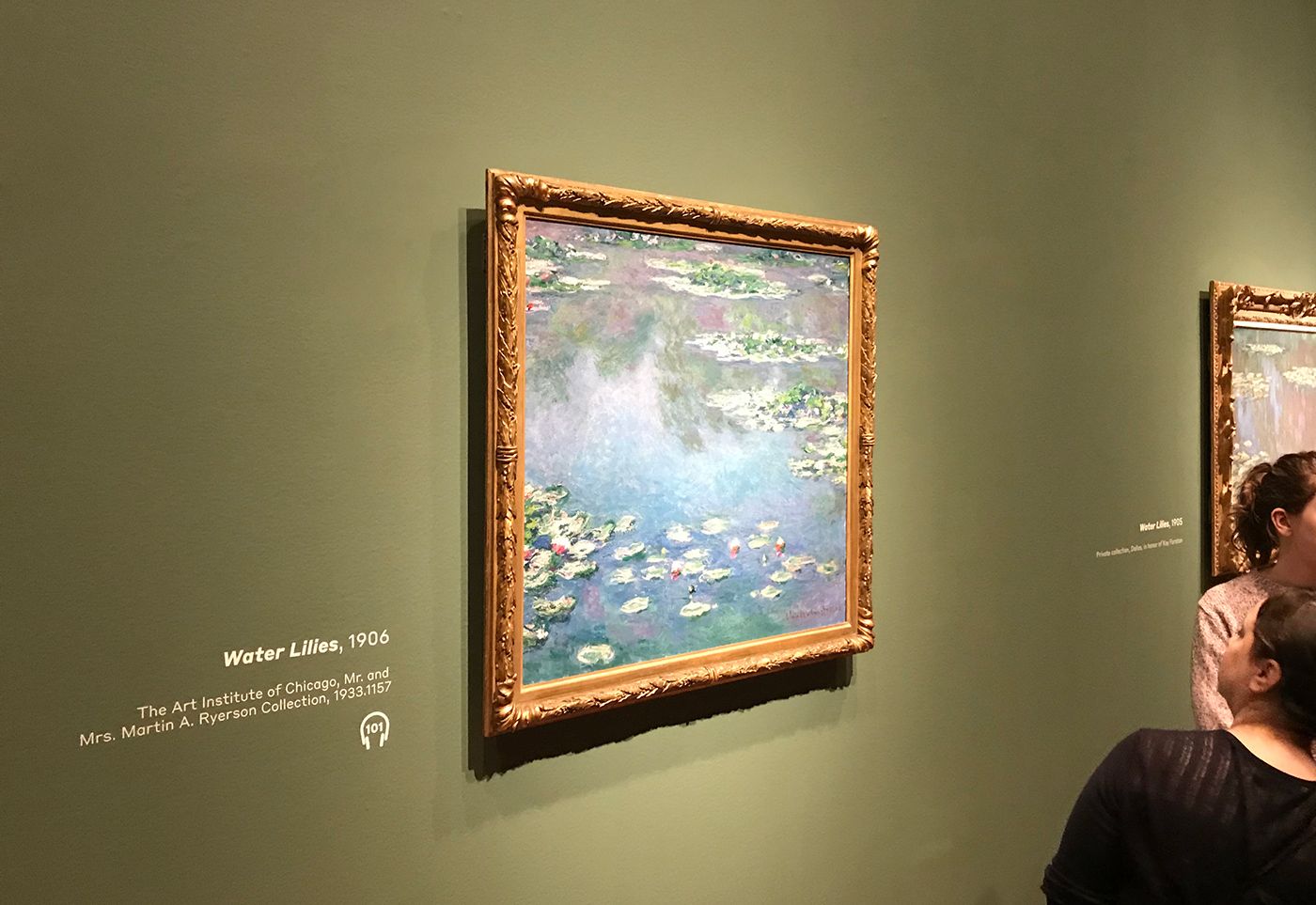

The first room in the gallery shows works Monet did in the period right after he settled in Giverny, France, northwest of Paris, where he began cultivating a garden and a pond full of water lilies, and built the iconic Japanese footbridge, which he would paint over and over again for the remainder of his life.

As the museum's curators note, this was Monet at his most polished and productive — not long after, in 1911, he lost his second wife Alice, and then he lost his eldest son Jean in 1914, who was married to his favorite step-daughter Blanche. It was in the period after this, as his eyesight was failing, that the majority of the paintings in this show were made.

2. Many of the works look vaguely unfinished

While lovely, this painting of roses is impressionistic even for Monet, and he did not paint to the edge of the canvas — leaving some of the canvas in the middle untouched as well. While this isn't odd for fans of the modernists who came after him, this does seem strange for Monet and one wonders if some of these albeit large pieces were, indeed, left unfinished in a corner of the artist's studio. (Most do not come from prominent collections, but were part of a single bequest from one of Monet's sons to the Musee Marmottan Monet in Paris.)

3. There's a painting from Dede Wilsey's own collection here

The grand dame of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Diane "Dede" Wilsey, no doubt had a hand in organizing this show so that she could hold up her own Monet against all these others.

4. There are some gorgeous, monumental pieces in this show that belong to world-class museums.

I don't know enough about Monet valuations to say whether his later works tend to command lesser prices at auction or not — and some of these works, in particular a couple of large water lily pieces, have been in museum collections for decades and we wouldn't know what price they'd command unless the museum decided to auction them. But in addition to pieces that seem unfinished there are some truly magnificent, wall-size paintings that need to be seen in person to be appreciated.

5. The curators are only guessing when some of these paintings were done

Though Monet occasionally included a year next to his signature, with some paintings he left us to guess, so many of these have date ranges like "1914-1917."

6. Things get downright psychedelic by the 1920s, when Monet was blind in one eye and had only 10 percent sight left in the other.

Abstract expressionism, indeed.

Fans of Monet should see this show for those final two rooms alone, when flowers, rose trellises, the famous footbridge, and a weeping willow tree all become very crazy looking.

"Monet: The Late Years" runs through May 27. Find tickets here.