You’ve perhaps heard during your Bay Area residency the occasional passing reference to an “Emperor Norton”, some foppish, overdressed, Victorian-era kook whose legacy we are apparently supposed to respect. Why? Why is Emperor Norton considered historically significant? What cultural influence has this ostrich-feather-hatted white guy on modern-day San Francisco? In honor of this Sunday's 137th anniversary of his death in 1880, SFist dug through Mark Twain-era newspaper clippings and anciently out-of-print biographies at the San Francisco Public Library History Center to determine who Emperor Norton was and why he is still considered iconic in contemporary San Francisco.

“He was the original eccentric, the original weirdo,” said Kevin DeMattia, one of the owners of the Tenderloin’s Emperor Norton’s Boozeland that is home to much of the artistic ephemera shown in this article. And while other cities around the world may have had weirdos who predated him, Emperor Norton was a Gold Rush-era bon vivant who combined the local-legend cult-following magic of Frank Chu, the crassly effective media manipulation of Donald Trump, and the inexplicable cultural staying power of a Kardashian to be the most talked-about San Francisco socialite of the earliest years.

This despite that Emperor Norton was flat broke and lived in the 1880s equivalent of an SRO. This is his story.

The Rise and Fall of Joshua Norton

Joshua Abraham Norton arrived in San Francisco in 1849 as a legitimately wealthy and powerful man (estimates on his age vary, but he was likely in his late 30s at the time). Norton had inherited his father’s South African shipping empire, and once in San Francisco he bought more ships, several parcels of land, and opened a successful cigar factory and rice mill. By 1852, Norton’s net worth increased to $250,000, or several million in today’s dollars.

Norton lost that fortune practically overnight over a rice deal gone bad. He bought a giant shipload with 200,000 pounds of imported Peruvian rice, thinking he’d corner the market during a severe rice shortage. But in the days to come, several more ships of Peruvian rice arrived on San Francisco shores, driving the price of rice down instead of up. Norton sued the rice merchants who he felt swindled him, but the courts ruled against Norton and his properties were foreclosed upon to settle his debts.

Nine years after his splashy arrival, Norton had fallen from high society, and was holed up in a crappy boarding house.

Bust of Emperor Norton in the upstairs of Emperor Norton's Boozeland (Image: Joe Kukura)

So He Starts Calling Himself ‘Emperor’

A massively high-functioning schizophrenic, Norton played on the anxieties of the Civil War-era suspicion of the federal government. In September 1859, he walked into the offices of the successful newspaper the San Francisco Bulletin and handed them a slip of paper, which he signed “Norton I, Emperor of the United States” and declared the following:

I, Joshua Norton, formerly of Algoa Bay, Cape of Good Hope, and now for the last nine years and ten months past of San Francisco, California, declare and proclaim myself the Emperor of These United States, and in virtue of the authority thereby in me vested do hereby order and direct the representatives of the different States of the Union to assemble in Musical Hall of this city, on the 1st day of February next, then and there to make such alterations in the existing laws of the Union as may ameliorate the evils under which the country is laboring.

The Bulletin published his decree as news, because why not. No one showed up at the Music Hall for Norton’s meetings, but his ludicrous decrees were an incredibly popular novelty and sold many newspapers. Competing newspapers seized on the tactic and also published any decree Norton would give them, and sometimes merely made up decrees and attributed them to Emperor Norton.

Norton wrote more decrees, and soon newspapers in other cities started publishing them, making him somewhat of a national star. Emperor Norton decreed the abolition of the US Congress, the California Supreme Court, and both the Republican and Democratic parties. When France invaded Mexico in 1863, Norton added the phrase “Protector of Mexico” to his title.

The man never set foot in Mexico in his life.

Sign at Emperor Norton's Boozeland (Image: Joe Kukura)

The Original ‘Don’t Call It Frisco’ Snob

While our city’s cultural elitism against use of the abbreviation “Frisco” is most frequently sourced to Herb Caen, the original ban on the term is generally attributed to a supposed 1872 declaration from Emperor Norton:

Whoever after due and proper warning shall be heard to utter the abominable word 'Frisco,' which has no linguistic or other warrant, shall be deemed guilty of a High Misdemeanor, and shall pay into the Imperial Treasury as penalty the sum of twenty-five dollars.

While that is cleverly worded, this quote is completely apocryphal and there is no evidence Emperor Norton ever said it or had it printed in his name.

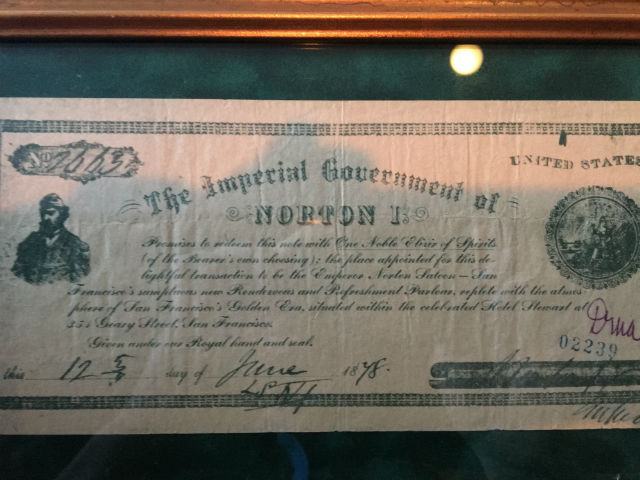

Emperor Norton currency on display at Emperor Norton's Boozeland (Image: Joe Kukura)

He Starts Printing His Own Money

Norton excelled at collecting freebies. Reporters, including then-Samuel Clemens (who would become Mark Twain), followed him around and reported on where he ate and which stores’ clothes he was wearing, just because both Norton and the reporters would get free hook-ups in exchange for the free publicity. Politicians sought Norton’s company just to bolster their popularity. Leland Stanford let Emperor Norton ride his trains for free, because Leland Stanford was widely hated at the time and needed some good PR.

Army officers happily gave Norton their uniforms, which he took to wearing about town daily whilst diligently collecting his freebies. He eventually started issuing his own money — which he sold for actual US currency, or used about town at businesses that gladly accepted it. Norton became a legitimate tourist attraction, and visitors would come to town just to meet him and buy his phony money. Norton claimed that holders of his currency would be paid back with 7% interest in the year 1880.

Conveniently, Norton died just a few days into 1880 so no one ever got repaid.

Mural at Emperor Norton's Boozeland, by Andrei Bouzikov and Andrea Casserly (Image: Joe Kukura)

The Death Of An Emperor

Emperor Norton continued to attend society functions, but he did not make it to the January 8, 1880 monthly meeting of the Hastings Society at the Academy of Natural Sciences. On that cold rainy night, Emperor Norton was on his way to that meeting but reportedly keeled over and died at what is now the intersection of California Street and Grant Avenue.

Norton was carrying about five or six dollars on him, which was his life savings. Several local businesses chipped in so he could have a dignified funeral, and the Chronicle estimated that 10,000 people came to see his body lie in state. Furthermore, his funeral procession was attended by an estimated 30,000, and reportedly stretched for two miles.

Emperor Norton was buried at the former Masonic Cemetery north of the Panhandle. When all of the cemeteries were removed from San Francisco in the early 1900s, his grave was transported to the Woodland Park Cemetery in Colma, where it still remains today.

The Emperor Gets A Widow, Posthumously

An amusing epilogue to Emperor Norton's story came in 1965 when pioneering gay activist and onetime San Francisco candidate for supervisor Jose Sarria donned some regal drag and declared himself Empress I, The Widow Norton, in a cheeky nod to both Joshua Norton's zaniness, and to the city's historic love of eccentricity. As Empress I, Sarria would go on to become the founder of what is now an international LGBT social and philanthropic organization known as The Imperial Council, which continues to elect local emperors and drag empresses every year in cities all over the country and world. Sarria died in 2013, and his grand funeral at Grace Cathedral was followed by a burial in Colma, near the grave of Emperor Norton.

For a fully immersive commemoration on the 137th anniversary of his death this Sunday, Emperor Norton's Fantastic San Francisco Time Machine will hold the Fourth Annual Emperor Norton Memorial Walk to retrace his final steps.

Related: Effort To Rename Bay Bridge After Emperor Norton Revived By Online Petition

Image: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library