As hundreds or even thousands of tech layoffs again become everyday news this week, we look back to the dot-bomb implosion of 22 years ago, when the Bay Area became a graveyard of f*cked companies.

In the mere first ten days of November, we’ve seen hundreds of layoffs at Lyft and Stripe, thousands of layoffs at Twitter, and more than 10,000 layoffs at Facebook/Meta. And if it hasn’t crossed your mind, a certain historic analogy has probably at least crossed your timeline: The SF Business Times is wondering “is the Bay Area headed toward another dot-com-scale meltdown?” The SF Standard notes, “wide-ranging layoffs have led to prognostications about a ‘dot-com 2.0’ bubble burst.” The Information has perhaps the cleverest wordplay of the bunch, in a conversation with the Secretary of the Treasury during that era Larry Summers, whom they say predicted “a level of pain he likened to the dot-com bust. ‘Peloton equals Pets.com,’ he said.”

But before we go off the ledge, it’s important perspective to remember that we’ve actually lived through this before, and we’ve lived through it quite recently. As Bloomberg observed Tuesday of this week, layoffs are “nearing levels seen in the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic.” Despite the media coverage, current layoff levels are just a fraction of what we endured in March and April of 2020 — though high-profile tech companies were perhaps spared then.

What’s happening in the tech sector right now has stark similarities to dot-bomb bust: It’s affecting the Bay Area more than the rest of the nation, it’s the downfall of “smartest guy in the room” founder types who were spoiled with years of uncritical media coverage, and the gig was essentially up when the venture capital billions ran out before even a smattering of profits ever appeared on the horizon.

Back during the dark days of the 2000-01 recession, we would wake up, toast one slice of Valu-Save white bread, pour some hot water over three-day-old coffee grounds, and peruse the latest news on a website called FuckedCompany. That site is not around anymore, but there are a few bits of it available on the Wayback Machine. It was an incredibly crude gallows-humor news aggregator about the latest layoffs, filled with unfiltered and unverified gossip, and gave profane, NC-17 nicknames to the companies it covered. (Remember how they referred to Accenture as “Ass-Enter?” That never got old!)

Like the current downturn, it was the aftermath of a bubble that peaked with a batch of money-wasting Super Bowl ads from companies that were drowning in VC cash, but had iffy-at-best business models. But different factors led up to this; a new generation of web browsers like Netscape and Mosaic made the internet accessible to regular folks, people were leaving their jobs to become “day traders” investing online with discount brokers, and a then-record 457 IPOs in 1999 seemed to offer guaranteed riches.

And these new boy-geniuses claimed to understand this “new economy” better than seasoned analysts. Consider the then-wildly popular Redwood City-based web portal eXcite, which was doing so well in 1997 they turned down the chance to acquire a new search engine for less than $1 million. That search engine was Google.

Remember these Webvan boxes? Do you still have any? Those boxes were sort of a symbol of the “new economy” model to just gave away tons of shit for free, under the growth-at-all costs business model where all that mattered was getting your name out there. Surely the revenue would follow! After all, Webvan had a stunning $178.5 million in sales in the year 2000. The problem was, as we learned when they filed for Chapter 11 the following July, was they had $525.4 million in expenses.

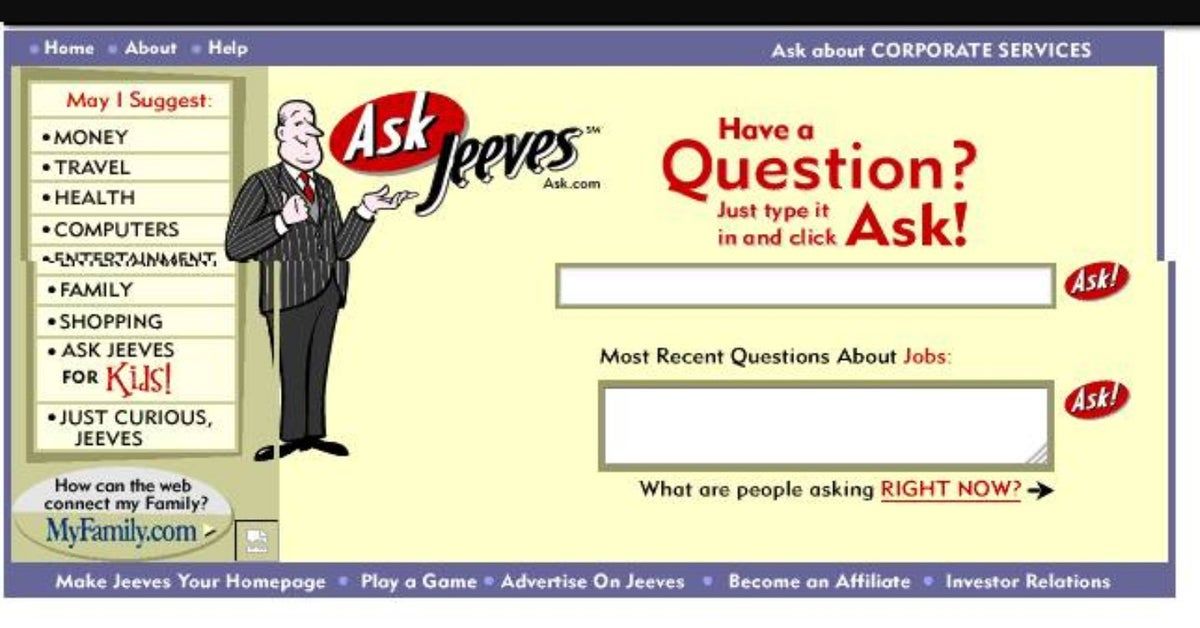

And oh, the dot-com parties! The above company, Emeryville-based Ask Jeeves, had Elvis Costello play at their April 2000 company party. “What you've got is a $1 million monthly tab for booze, food and music, all of it paid for by the new economy,” Slate wrote at the time. “Never before, not during the textile, transportation or steel booms, have companies spent so much money on people who don't work for them, and who often have only a passing interest in the company.”

Booking Elvis Costello seemed fine — after all, Ask Jeeves’s stock IPO’d in 1999 at $14, and was at $77.81 by the end of that day. It would climb to $190 a share by December 1999, but within 18 months, it would be trading at 86 cents a share. (Everyone remember when Facebook and two other companies all threw un-ironic Great Gatsby-themed holiday parties in the heyday of 2015?)

Amid the irrational exuberance, the tech-heavy NASDAQ index hit an all-time high of 5,048.62 in March 2000. But it would fall 35% in just a month, as the failure to produce profits started the grim reaping of mass layoffs across the Bay Area, and the recovery would take years. The NASDAQ would not reach 5,000 again for another 15 years.

Tens of thousands of laid-off Bay Area employees, those of us who stuck around, at least, tried to make the best of it. Something called Pink Slip Parties became a craze for the newly unemployed. “Those sacked are given a red dot to wear, those who can offer jobs a green dot, and those who just want to party — the laid back rather than laid off — get a yellow dot,” the Guardian explained in January 2001, using proper British lingo. “The parties are now held monthly, entry is free, and the bars in which they are held charge redundancy-friendly prices: $2 (£1.35) for a pint of beer or a martini cocktail.”

The degree of job losses in 2001 was far beyond what we’re seeing right now. Two million people were laid off in 2001, per the Silicon Valley Business Journal, as the dot-com bust led into the economic shocks of the September 11 attacks, and to a lesser degree, the Enron and accounting scandals.

So, the current tech downturn now is nowhere near the scale of what happened in 2000-01 — at least not yet — or for that matter, what happened during the Great Recession of 2008-10, or the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the dot-com bust, companies went belly up entirely, putting gluts of office furniture on the market. In the current slate of layoffs, established companies are merely downsizing. In fact, some are only downsizing to pre-pandemic levels, after tech companies made bank while the broader economy suffered mightily. Consider Facebook, which did just lay off 11,000 people, but grew its staff by more than 20% over the course of the pandemic.

And we can’t help but notice another factor: The bloodletting has been the worst at companies that invested big in this nebulous concept of Web3. Companies that sink millions into crypto, blockchain, and decentralized metaverses have pretty much lost their shirts lately. Who knows, maybe this Web3-whatever will work out to something someday, the same way that "dot-com" businesses eventually became the way of the world and not just novelties advertising during the Super Bowl. But any new form of the web might not even resemble the current dreams of crypto evangelists, and it might not even be called Web3.

In fact, in the future, “Web3” might become the short-hand term that proves every bit as negatively loaded as "dot-com bubble."

Related: Twitter Evokes Dot-Bomb Memories With Pricey World Series Ad Campaign [SFist]

Image: The pets.com sock puppet dog stars in a commercial for the company, Los Angeles, California, January 11, 2000. The San Francisco-based pet products company announced on November 7, 2000 that it was shutting down after failing to secure a financial backer or buyer. (Photo by Bob Riha/Liaison/Getty Images)