Keeping track of where the Omicron variant has already spread and how quickly it may be multiplying is just the latest challenge for scientists and public health officials — and perhaps the only reason the first U.S. case was found in SF is because of the caliber of the health system here, not because it isn't already in other places in the country.

A person sick with COVID landed at SFO before Thanksgiving, on Monday, November 22. That person had been in South Africa, and within days began feeling ill. A lab at UCSF would not receive the person's "suspicious" test sample until Tuesday afternoon, November 30, eight days after their arrival in the country, and after an unknown number of encounters with friends and family. The sample appears to have been taken by a Color Lab in SF on Monday the 29th, and other samples may still be being processed from the person's close contacts — but the CDC said those contacts have so far tested negative.

It wouldn't be until 4 a.m. Wednesday that researchers at UCSF could confirm with certainty that this was indeed an Omicron sample, and that was after working through the night with special urgency.

An earlier report by CNN reported that the positive test had come in on November 29, but now we are learning just how long it took for that test to be flagged and have its genetics sequenced.

"This particular sample, I heard about it yesterday at about 3 p.m.," said UCSF's Dr. Charles Chiu at Wednesday's news conference at SF City Hall, per KPIX. "We were able to receive the sample in the laboratory by 8 p.m. We ran a very fast molecular test which looks for spike gene dropout. What this test can tell you that you may have detected omicron, but it’s not conclusive."

It would be a total of 30 hours between the time of the Color test being administered to it being sequenced and fully confirmed, as the Chronicle reports — though that timeline seems odd if 4 a.m. was the final confirmation, which would put the test at 10 p.m. on Monday night. Maybe 10 p.m. Monday was when the test positivity was first confirmed?

"We were able to confirm the detection of Omicron in five hours and had nearly the entire genome in eight hours," Chiu said. "At 4 a.m. last night we were able to conclusively demonstrate that this was an infection of the Omicron variant."

It's likely that within days, or even before today is out, we will hear of other cases in the U.S. — and given the efforts described above to sequence a single sample, is it any wonder that this should take a little time after the world first heard about Omicron just five days ago?

The US is better than many countries at detecting and sequencing variants, and it has only become so in the last six months or so. Still, as Kristian Andersen, a professor of immunology and microbiology at California’s Scripps Research Institute, tells Vox, it's still an ad hoc network of labs that is doing the heavy lifting. "A lot of it is still hacked together," Andersen says of the system.

Andersen further explained that it was both the high prevalence of Omicron in South Africa as well as South Africa's better-than-average system of surveillance for variants, that led to its discovery there.

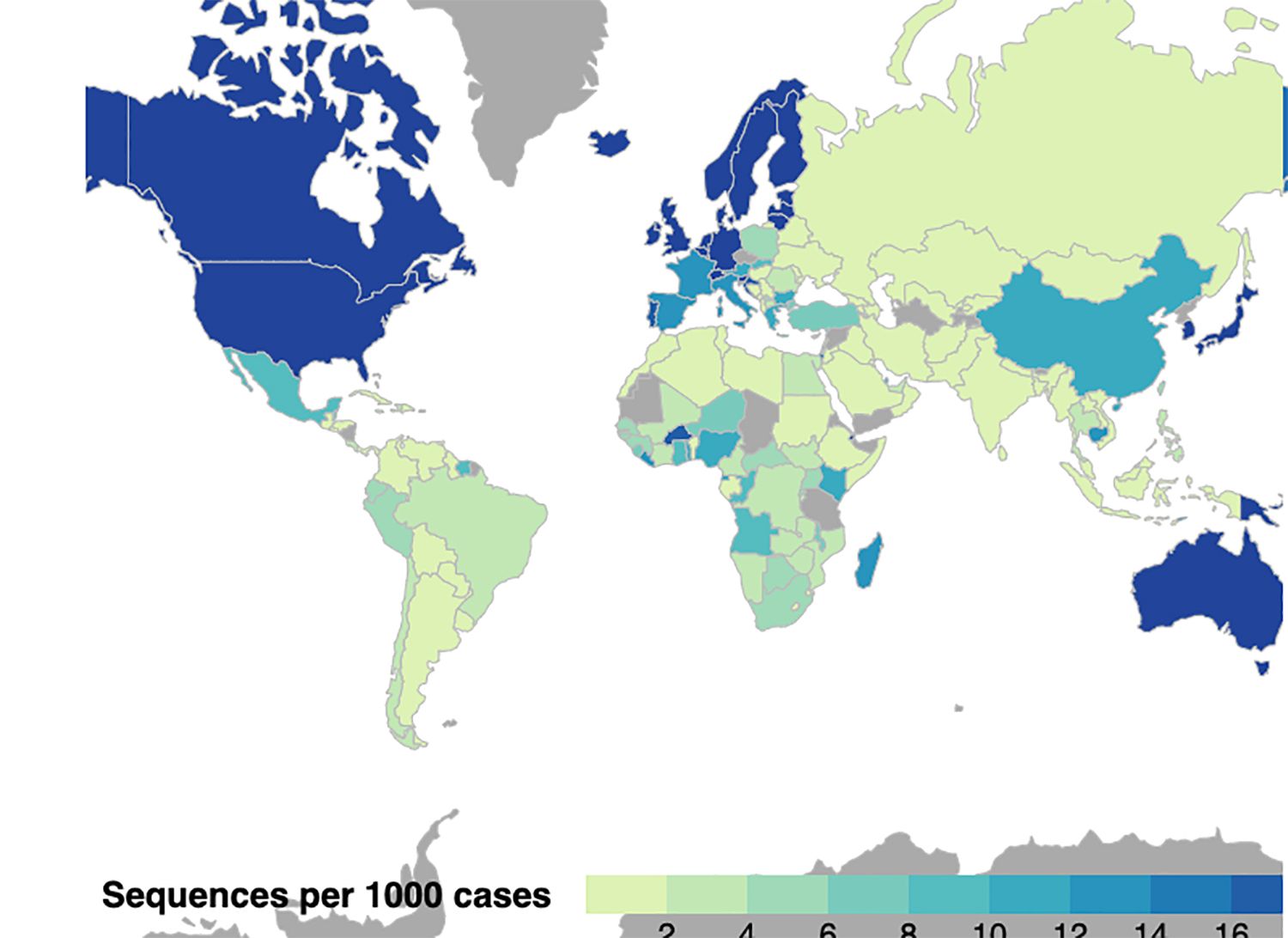

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky said Tuesday that the U.S. is now running genetic sequencing on one out of every seven positive COVID cases in the country — though this global database is still saying that the U.S. only runs 29 sequences per 1,000 cases, which would be one out of every 34 cases. That still puts us in the top 20 countries globally, as Vox reports, but it highlights how many variant cases could be slipping through each day, with the U.S. now finding about 50,000 to 120,000 new COVID cases each day.

The fact remains that no one knows if Omicron is better at evading vaccines or spreading more easily than Delta, it just appears it might be. Evolutionary selection is likelier to have given rise to a variant that is successful at something, however as the New York Times reported Monday, experts caution that mutations can also work against each other, and it's still early days with this variant.

The infected U.S. individual, a San Francisco resident, had two doses of the Moderna vaccine, likely more than six months ago — but we don't know the dates. That person had not yet received a booster.