In terms of wildfires in Northern California this year, it's not a matter of if but a matter of when, where, and how terrible. That's according to new maps showing the extreme fire potential taking shape with dry fuels across the region, and one fire weather meteorologist who is watching it like an approaching storm.

First, the good news: Because the northern part of the state received so little rainfall this spring, grasses didn't grow in quite as fully and densely as they did last year, which means that vegetation fires on grasslands will hopefully be smaller and easier to control.

But the bad news is really bad, as expert Stephen Leach tells the Chronicle this week. He's a fire weather meteorologist with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management who forecasts the wind events and other high-risk situations for wildfires in our region. He says one added risk from the below-normal rainfall is that there are more dead outer branches on trees and brush, creating more fuel.

The lack of rain, especially in April, has led to an accelerated process of "curing," which is when green vegetation dries up and becomes fuel for fires.

"All areas of Northern California are vulnerable for wildfire spread now, several weeks ahead of normal," Leach tells the Chronicle. "The higher-elevation timber areas have the dry fuels in place, and ignitions are becoming a bigger threat for large fire occurrence. At lower elevations, including the Bay Area, trees and brush are very stressed and will become flammable a lot earlier than usual."

Ignitions obviously come from a variety of sources, most of them human-caused. But Leach says the worst-case scenario in 2021 would be the same as what happened in mid-August 2020, a massive array of lightning strikes all at once — something that's relatively rare for this part of the world, thankfully.

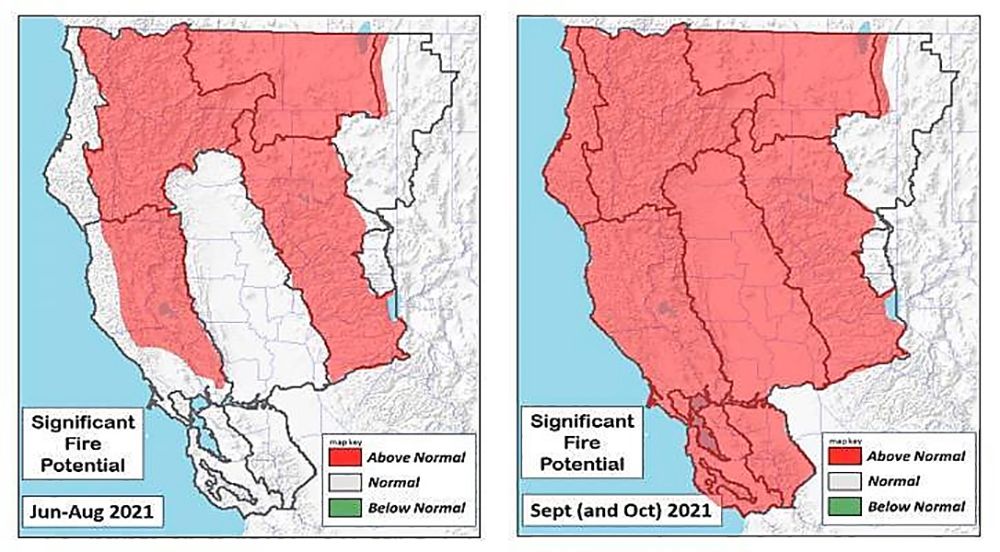

The maps below from the interagency Northern California Geographic Coordination Center show the scary situation developing for late summer. While parts of Napa and Sonoma already show above-normal fire potential taking shape between June and August, the entire Bay Area turns red — indicated above-normal fire risk — by September. That includes San Francisco (though the city isn't dense with the kind of brush and trees near power lines that create the greatest fire risk).

The signs of this year's grim reality to come are already lining up, starting with the extra-early Red Flag Warning that was declared in the first week of May.

"In a better scenario, we wouldn’t be dealing with this until the traditional fire season in the fall," said National Weather Service meteorologist Gerry Diaz, speaking to the Mercury News at the time.

And while brush fires around the Bay Area in recent days have been quickly contained so far, it only takes one happening on a windy day to create a catastrophe. On Thursday, a fire of unknown cause spread through grass and oaks in Novato, growing to three acres and threatening some homes before being tamped down.

"The level of concern [this year] is through the roof," says Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at U.C.L.A. and the Nature Conservancy, speaking to the New York Times this week.

Climate change is clearly a culprit in what's happening, given that the the 10 largest wildfires in recorded California history have all happened since 2000. And we may have climate change to blame for things like last year's lightning siege, and the increased frequency of wind events that down power lines.

A 2015 study suggests that California doesn't have just a single fire season in summer, but two fire seasons that pretty much take us through the entire year, minus the month of May. The study, co-authored by University of Missouri-Kansas City geosciences professor Fengpeng Sun, suggests that one fire season between June and September is driven by inland summer temperatures and lack of rain, and those fires tend to be further from the coast, often in remote places. But the most destructive fire season lasts from October to April, Dr. Sun and colleagues suggest, and it is driven by wind.

The Santa Ana winds have been the culprit in many Southern California fires, and in Northern California we have the twin phenomenon of the Diablo winds. The winds are created when air flows down from Nevada and Utah and drops from an elevation of around 4,000 feet, compressing as it gets pushed down to sea level. This creates strong gusts of over 50 miles per hour over the tops of mountain ridges, like those that ring the Bay Area.

A Diablo wind event was responsible for the Camp Fire, the conflagration that destroyed Paradise, California in November 2018. And these winds fueled the Glass Fire last fall, which went on for three weeks, burned around 20 wineries in Napa, and destroyed over 300 homes in Napa and Sonoma.

In the end, though, wind doesn't cause fires. People and power lines do. And here's hoping everyone — and PG&E — manage to EXTRA cautious this year.

"California has a lot of people and a really long dry season," says Dr. Park Williams, a bioclimatologist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, speaking to the Times. "People are always creating possible sparks, and as the dry season wears on and stuff is drying out more and more, the chance that a spark comes off a person at the wrong time just goes up."

Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images