Sometime during the six or so hours of watching and listening to Gatz at Berkeley Rep, I found myself contemplating deep questions about death, how we honor our dead, and how perfectly crafted stories like The Great Gatsby make a short-lived existence like Jay Gatsby's feel meaningful.

It's the power of F. Scott Fitzgerald's 95-year-old novel, which still feels deeply resonant, and relevant, despite some casual racism and a plot that hinges on a perhaps overly romanticized love. And in order not to compromise any of what Fitzgerald was after in his tightly composed prose, the theater company called Elevator Repair Service began developing their production, Gatz, over 20 years ago using the entire book, word for word.

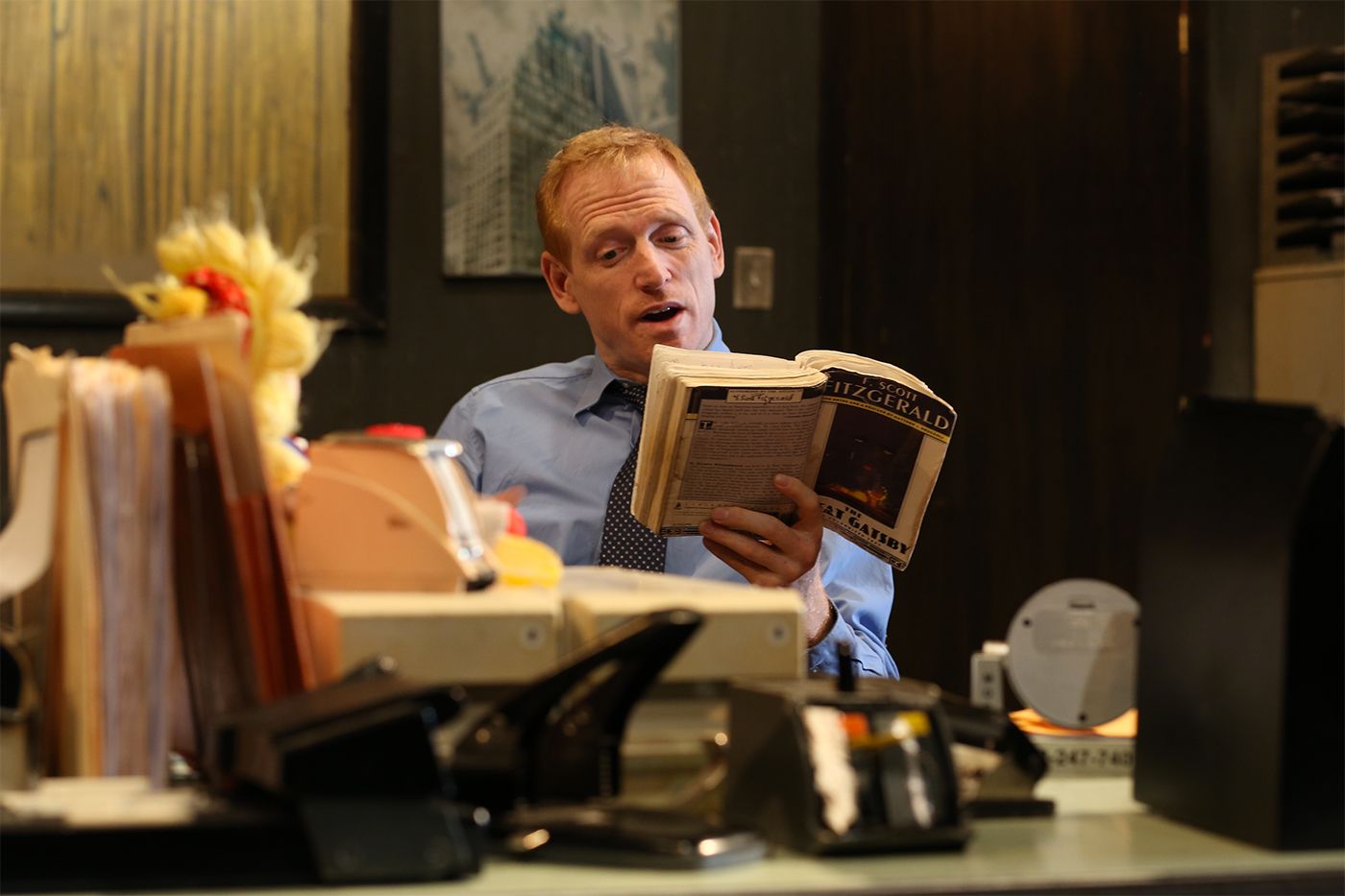

The show begins in a drab office setting. Scott Shepherd, who has been portraying our narrator Nick Caraway in productions of Gatz dating back to 2005, sits at his desk trying to make a computer turn on, and in an old rolodex he finds a worn paperback copy of The Great Gatsby that he begins reading aloud. Fitzgerald's text is heavy on the exposition in its first chapter, so we only hear Shepherd speaking for a long while. Other actors move in and out, occupying desks and a couch in the office, doing tedious things and moving file folders around, and having inaudible conversations, but Shepherd keeps reading, even as the dialogue begins when Nick is first invited over to the Buchanan house in East Egg, on Long Island for dinner.

But then a male actor, one who had been fading in and out of the office tableau, suddenly speaks one of Tom Buchanan's lines: "Civilization is going to pieces." It's a shock to suddenly have a new voice in the story, and the moment opens the door for the rest of the piece, in which actors move on and off the stage, assuming most of the dialogue, some portraying single characters throughout and some portraying many. As directed by John Collins, this version of The Great Gatsby isn't a staged reading so much as it is an experiment in bringing a book to the stage, and a piece of theater about reading itself.

One moment you're just absorbing words from pages, flipping those pages, thinking about the words. The next moment you're transported to a mansion on Long Island in the early years of Prohibition, casually flirting with a lady golfer with "grey sun-strained eyes."

The scene that exemplifies the magic of Gatz most gloriously comes in the second chapter, when Nick accompanies Tom on a trip into Manhattan with his mistress Myrtle. As the characters get drunker, and as the apartment party devolves into chaos, Nick continues narrating while also becoming drunk himself — and Fitzgerald's pitch-perfect descriptions of the boozy, later hours are well matched with company's performance of escalating drunkenness. "I was within and without, simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life," Fitzgerald writes. And rather than simply having the scene dramatized, as has been done in two Hollywood films and countless other adaptations including an opera, we get the pleasure of all of Fitzgerald's words. The plot and the dialogue were never the most important parts of The Great Gatsby, after all. It's the poetry of Fitzgerald's text, coupled with his meditations on class and ambition and the American experience, that make this a great work of art.

Shepherd has said in interviews that the company chose to perform the novel this way because every time they tried to cut something it felt like "some violence" was being done to the work. And Collins says in a program note that Gatz came about because they realized that Fitzgerald's prose "is so delicately and expertly constructed that even the omission of a single adjective is rhythmically disappointing."

It's clear that performing the novel is an act of reverence and love for this cast. Robert M. Johanson does particularly memorable work as Tom; Laurena Allan and Frank Boyd are marvelous as Myrtle and George Wilson; and Annie McNamara is terrific as Daisy.

Having been performing this piece, off and on, for 15 years, these actors bring a gravitas to the text that wouldn't be possible with younger performers — and it struck me how young Fitzgerald's characters all are. They speak wisely for people who are all just around 30 years old, but they are all just around 30 years old — speaking wearily about what the world has already shown them.

I've read this novel three times, yet I was still struck by many passages as if I were hearing them for the first time — and, indeed, I was, because I was previously only "hearing" them in my head or reading them too quickly and skimming past the beauty of certain turns of phrase. Also, it's incredibly funny! There is more humor in this novel that comes out on the stage more than it ever jumped out at me on the page — though of course, a few characters including Myrtle are obviously tragi-comical.

That is ultimately the mission of Gatz — to dramatize, in some sense, the act of reading itself, and the way one can be swept up in a novel and the world of images that's conjured by a novelist's words. And the play succeeds on that level as well on the level of creating a compelling piece of theater — albeit an epically long one. What better way, though, to ensure that you don't miss a single word?

Gatz plays through March 1 at Berkeley Rep. Find tickets here.