Earlier this week, the Dow Jones Industrial Average suffered its largest intraday loss in history. With it, several major Bay Area stocks sunk low. Shares of Twitter dipped below their IPO price, and talk inevitably turned to the long-expected "market correction" (as it's euphemistically referred to in these parts). Executives and investors agree that such a shift, or more dramatically, a "winter is coming." If so, what would the weather be like in San Francisco, so to speak?

We're going to do our best, via the past experience of Bay Area residents in different sectors, to answer that question. After all, winter here can be warm and lovely, or cold and foggy, or who knows what.

Typically, it's science fiction that presents us with strange future worlds to explore, different from our own after assumed environmental shifts, wars, and subsequent economic and technological changes. In much the same way, we can only guess as to how the next phase of San Francisco's economy will look, and it could be impacted not just by a tech bubble but also by a persistent drought or an inevitable earthquake. But, as in the world of speculative fiction, how a new San Francisco might look down the road —and what it might be like to live in — are maybe more valuable questions than what precisely happens in the very near term.

Employment

It's been said more than enough times that San Francisco is a boom-and-bust town, and of course the Bay Area has something of a recent "test case" in the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s. A former Yahoo! employee, once worth $2 million on paper, tells SFist he left town broke at the end of that era. “The stock price had been going up and up and up and splitting and going up,” he said. “People used their stock options as their paycheck. They didn’t really care what they were getting paid [in salary]. Then people’s stock options started going underwater.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, "[f]ollowing the peak of the high-tech boom, employment in Silicon Valley high-tech industries declined by about 17 percent, representing a loss of slightly more than 85,000 jobs."

Another former dot-commer, Antone Johnson who worked for Excite — a Yahoo! rival which employed 3,000 workers and had $600 million in revenue at its peak in 2000 — wrote in to Quora to set the scene after the crash.

"The collapse was sudden," as he describes it. "[S]hocking, and depressing.. I think most of us saw it coming, but the speed and severity came as a hell of a shock."

"It seemed like everyone I knew in their 20s and 30s was working for a dot-com. (That should have been a warning sign right there.) Not just San Francisco Bay Area locals; new college grads and experienced business and technology professionals were migrating here from all over the country (and world) in the years leading up to the crash. Commentators famously compared it to Florence during the Renaissance."

Rents and Housing Prices

"The housing market was beyond ridiculous at the peak [in 2000]," says Johnson. "I mean worse than the usual 'Bay Area ridiculous' that's been the status quo since the 1980s. (People were resorting to paying six months or a year's rent in cash in advance in order to get a decent apartment in San Francisco, CA.)"

Sound familiar? Though San Francisco's median rent has been put at a likely exaggerated $4225, there is no doubt that our housing prices are way, way high.

Rental and home ownership markets, though, have behaved differently during past boom-and-bust cycles. Rental prices have gone down during hard times, whereas home prices have typically plateaued.

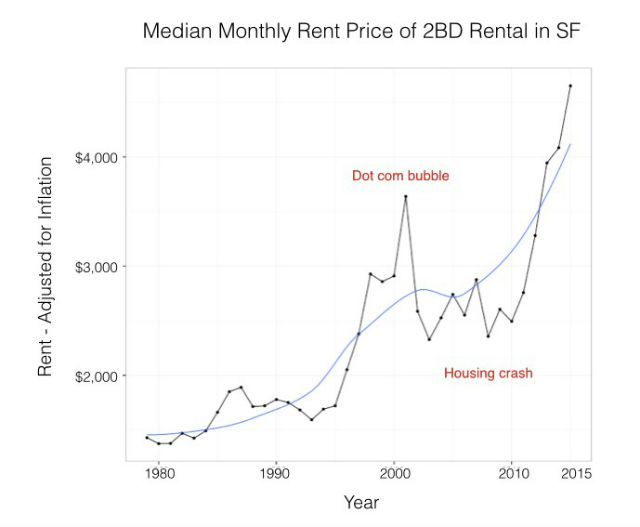

The above graphic comes from Greylock Partners’ community lead Chris McCann’s Medium analysis 1979 to 2015 — Average rent in San Francisco. These numbers, inflation-adjusted into 2015 dollars, show that rents for a 2-bedroom apartment in San Francisco have drastically gone up during bubble phases and down during crash phases.

Of course, this doesn’t mean your landlord is going to reduce your existing rent when the economy sours. It means that if you vacate your apartment when it does, the next tenant is likely to get your apartment offered at a (slightly) lower rate or they will use the old landlords' trick of giving you one month free, keeping the same high rate.

Home prices, for their part, have not fallen as drastically during crash phases. Paragon Real Estate Group’s report Thirty Years of San Francisco Real Estate Cycles shows just a 10% drop in Bay Area home prices in the year following the dot-com bubble, and a 27% drop over the three years during the Great Recession — drops much less steep or sudden than the rental price declines. I should note that this home price data also includes San Mateo and Marin counties, not just San Francisco.

Jonathan Dearman, a San Francisco native and for 20 years a realtor here, spoke with Mission Local in April on the steps at 2709 Bryant Street, the site of an open house. “Everyone thinks there’s this bubble that’s going to break,” said Dearman. “It’s a real fear and concern, but I don’t think that’s going to happen in the housing market, because there is just a lack of space.”

Harry Clark, a broker with Zephyr, invokes the 2008 recession. “Everyone loves to talk about a bubble but the last bubble burst in 2008, and it only took San Francisco five years to come back even stronger than it was before This market in this city has always been more resilient than any other community."

“There’s just not a lot of inventory,” says Roxana Melgarejo, who works for Vanguard Properties, and that's been the perennial problem since demand never goes very far down.

Restaurants and Bars

As we know all too well, rent isn't the only place where San Francisco's riches end up. These days, we spend our money in Bon Appetit's "Best Food City In America." But is that accolade and our booming food scene a reflection of our current economic moment, and something that might change with a bust?

Of course, people still go out to eat and drink during a recession. One noticeable change: They don't tip as generously.

“Tips start going way down,” said Kilowatt bartender Marty Sullivan, who’s tended bar there since before the Great Recession. “You’re making like 30% less.” While business and tips at nightclubs suffer during a tech downturn, the current boom cycle seems to have seen the largest number of iconic bar closures, or pending closures, due to real estate prices.

Highbrow culture experiences a downturn as well. SFist's sources at the SF Ballet and Symphony noted that attendance went down during the 2008 recession because casual fans and dabblers stopped attending. At that time, though, such cultural institutions were able to reach a new demographic of bargain customers with emerging ‘daily deals’ sites like LivingSocial and Groupon, which have now pretty much bitten the dust.

Chef-owner Craig Stoll opened Delfina in the middle of the dot-com boom in 1998, and his restaurant weathered the storm in no small part thanks to its exceptional food. "There are a lot of restaurants," he told SFist outside his 18th street storefront, "competition is something we're feeling, but more than competition for customers, it's competition for staff. That's what happens during the boom: The cook shortage is real, and we can't pay people enough to live in the city and work in restaurants, so this is the biggest problem facing us. We can't staff our restaurants. That's not because of the bust, that's because of the boom."

Though "the audience" to support the local food scene has certainly boomed according to Stoll, the restaurant market, as Stoll sees it, isn't dependent on the tech one.

"The [restaurant] market corrects itself," he says. "If your restaurant isn't great, and even if it is great and it doesn't resonate with the public in an amazing, intense way, you're not gonna make it. Valencia is saturated with restaurants. Not only that, you have to make sure you have a good deal as well. If you're rent is too high and your model's broken, you're not gonna make it."

The same might be said of a high number of startups, particularly those with high burn rates who are tearing through their runway.

Techies Get Humbled, and Some Will Flee

Perhaps the biggest impact, for many, will be emotional, and will be a notch in the adult-experience belts of many young people earning big salaries that may not be sustainable in a "corrected" market. Just like during the dot-com bust, that could mean a population dip following our recent, tech-fueled boom, since some will no longer afford those $3,000 studios they just rented.

Talking to a group of friends at various large tech companies this weekend about this subject, few expressed concern for themselves. Companies, they implied, would consolidate, and large, established ones would remain major employers. But which side of the line are some startups on? That remains to be seen, or at least according to Antone Johnson, that's the way it went in the dot-com crash.

"Gallows humor pervaded for a while — people held 'pink slip parties' to make the most of the situation, and begin networking in search of the next job." In that spirit, some will likely recall FuckedCompany, the popular corporate death-watch website that tracked the demise of many a dot-com startup with a certain glee.

But, continues Johnson, "It soon became apparent to many that there were far too few jobs to be had. Stories appeared in the newspaper of net out-migration from the Bay Area for the first time in living memory; there was a U-Haul shortage (no joke) as people rented them for one-way moves back to Las Vegas or Dallas, TX or wherever the economy was healthier to get a regular job. Enterprising promoters held raves in the abandoned former headquarters of failed dot-coms (including ours). Bankers, lawyers and accountants who'd struggled to hire fast enough during the boom found themselves with a large number of highly paid workers with nothing to do."

Still, a lot of young tech workers don't have contingency plans. When asked about their "emergency" or "backup" ideas by Re/code, pretty much every tech founder interviewed dodged the question and bragged about the viability of their project no matter what.

Our Yahoo friend’s advice to today’s wealthy young San Franciscans? “Your lifestyle is going to change very quickly and very drastically. If you have cash in hand, look outside of the Bay Area, outside of California, and buy land somewhere. I kick myself for not doing that. Buy a house in upstate New York or upstate Oregon.”

Others, though, would prefer to stay. Some even incorporate the fear of failure — or crash, or simply the unknown — into their startups and/or life strategy in valuable ways.

"The Mission has been colonized by pigs with money," read a 1999 leaflet from the Mission yuppie Eradication Project. "They help landlords drive up rents, pushing working and poor people out of their homes."

But according to the Chronicle, such admonishment didn't deter current Bernalwood blogger

Todd Lappin. A '90s dot-com arrival, Lappin is now in his late 40s, owns a home, and still works in tech as a product manager at Flipboard.

"It's not easy to stay," said Lappin. But he sounds glad he did.

Looking at this 2001 piece in the New York Times, titled "A City Takes a Breath After the Dot-Com Crash; San Francisco's Economy Is Slowing," there are a few more tidbits that could count as predictions: cabs saw 25-percent drops in fares (these days that will impact UberX and Lyft drivers too), those looking for apartments were able to negotiate lower rents sometimes, but those trying to sublet rooms or find roommates may run into trouble. 26-year-old Courtney Vaughn is quoted saying that she posted a room for $800 on Craigslist, and "A year ago, it would have been the deal of the century. [But] I listed the apartment at 9 a.m., but by 2 p.m., it was already on the second page that means at least 100 people had listed after me.''

Pretty much everyone, though — besides landlords — will likely breathe a sigh of relief if they no longer have to do battle to find a place to live. Just remember: As history teaches us about this town, those respites never last long.

Additional reporting for this article by Joe Kukura

Image: Chris McCann via Medium