With the American premiere of the fourth season of Downton Abbey on Sunday (we know, you and your clever friends downloaded it via Britain months ago) came a new round of reviews in which critics are still trying to understand why Americans are obsessed with repressed, patrician, snobby English society. But as Maureen Dowd points out in her NYT column, you don't have to look much further than class dramas playing out on San Francisco's streets between Silicon Valley gentrifiers and the urchins they're forced to step over to get to their new mid-Market offices.

We're getting about as tired as you are about the incessant pontificating about the current tech-driven boom in San Francisco. But in light of last month's anti-compassion rant by tech dude Greg Gopman, Twitter's tone-deaf co-opting of City Hall for their holiday party, and the subsequent fresh maelstrom of national press about the attacks on Google shuttle buses, maybe it's not impertinent to look at what's happening in the context of class struggles of the past.

Below, a few comparisons that make some sense between today's Bay Area-specific, tech-related tensions, and the tensions of the rapidly modernizing, 1920s England as depicted on PBS.

While Manhattan is being taken over by bankers and hedge-fund managers raking in ridiculous bonuses, San Francisco's new-monied titans are from the more casual, slightly less douchey tech industry. But don't tell that to Denise Hale, who, like Maggie Smith's character the Dowager Countess prefers to talk to you if you're civilized, and you don't do vulgar things like spray good champagne all over your yacht. Also, how many times has Smith's side-eye reminded you of Hale's? (P.S. Hale has one of the main funders of Downton Abbey on PBS.)

Complainers like Greg Gopman and Peter Shih, bitching about the unwashed lower classes they're forced to contend with, sound a lot like the Crawleys when they bemoan the "Irish question" over a glass of fine Bordeaux at dinner.

(Photo via SFist tipline)

Poor unfortunate Molesley is just your average out-of-work front-end programmer with ca. 2002 HTML skills who everyone takes pity on but no one will give him a job.

Photo: PBS

Peter Shih complaining about start-up bros is kind of like Nanny West condescending to Barrow: You're all just somebody's employee, yo.

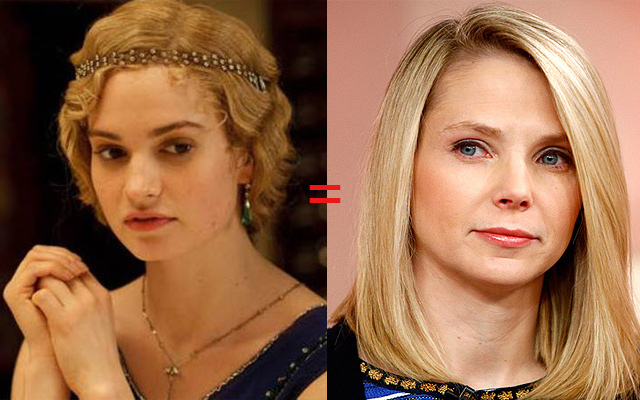

Melissa Mayer is so Cousin Rose.

Shirley MacLaine's Martha Levinson is so Pat Montandon!

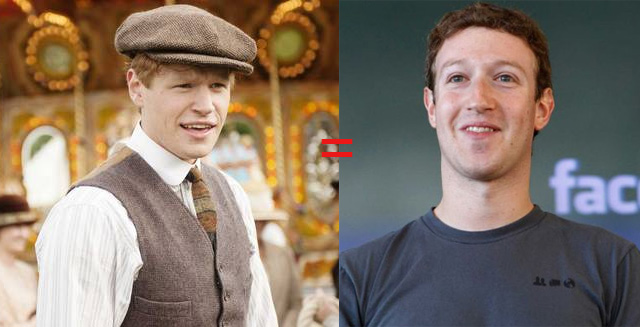

Mark Zuckerberg is so like goofy Alfred, if Alfred were less sweet.

Mrs. Patmore's reaction to the advent of the electric mixer, and Countess Crawley's reaction to the advent of the telephone, is pretty much how we all feel about Google Glass.

And the protests against corporate shuttle buses and Ellis Act evictions in San Francisco can be seen in parallel with the class and housing struggles of the day, with the Crawleys serving as landowners who can willy-nilly sell (and evict) poor tenant farmers, as they're contemplating doing this season in order to pay for Mary's death duty on Matthew's estate.

Anyway, sure, some of it's a stretch. But landed gentry! Great income inequality! Why do we fetishize these things? Is it just because the clothes are pretty and we all long for a simpler time when servants happily labored in the bowels of great mansions and everyone treated each other politely? Most historians of the age would tell you that servants didn't have it as good back then as Downton's seem to, and they all were a lot less well treated. As Niall O'Dowd of The Irish Voice recently put it, "For this generation of Americans, the ‘Downton Abbey’ ‘Yes, m’Lady’ servants are the equivalent to the old minstrel shows on the Bowery. It reflects the colonial cringe, casting an ameliorating light over a period that was full of pretty desperate stuff for people trapped in a rigid, notorious caste system."

[NYT]

Right: Denise Hale givingt side-eye in Vanity Fair to Larry Ellison.