The largely racist legacy of single-family zoning took a blow this week when Berkeley's city council voted unanimously to make moves to change its general plan and eradicate such zoning — a little over 100 years after the city became the first in the country to establish a single-family-zoned neighborhood reserved for whites.

For Berkeley, this is a necessary step to undo one of the last vestiges of racist planning practices — which were once more explicitly designed with segregation as a goal, with racially restrictive covenants and so-called "red-lined" maps. But single-family zoning was something Berkeley pioneered in the Elmwood neighborhood in 1916, and the effects are still being felt today, city councilmembers said, as the city's Black population has continued to be pushed out.

"It’s certainly not going to happen overnight, and I don’t think I’ve indicated otherwise,” said Councilmember Lori Droste at Tuesday night's council meeting, per Berkeleyside. “But [the resolution] is symbolic in stating that we want to address systemic racism. We can’t address racial and economic segregation unless we address zoning reform, that’s definitely true."

The council expects to complete the lengthy and complicated general plan change process in two years — and similar changes that up-zone neighborhoods for greater density and more affordability are taking place across Oregon and in the city of Sacramento. A task force in San Jose has also recommended studying the idea, but a statewide bill that would have made building duplexes and multi-unit buildings on single-family lots much easier failed in the state Senate last year.

Housing advocates have long said that such zoning changes are no quick fix toward housing affordability, without broader efforts to protect renters and support mixed-income housing.

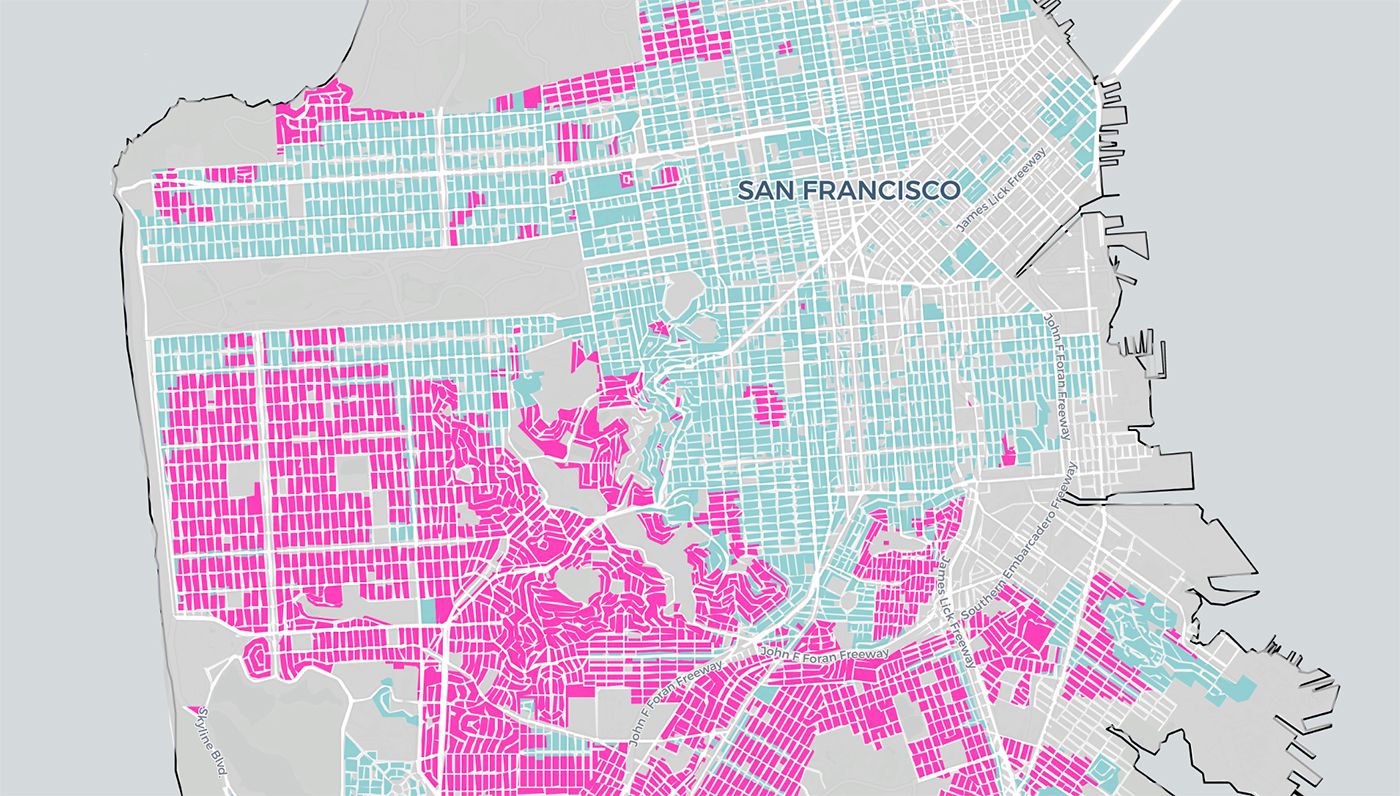

In housing-starved San Francisco, we are decades late in facing the fact that we live in a city that was developed half as a suburb. As the map below illustrates, from an October 2020 study by UC Berkeley's Othering and Belonging Institute, much of San Francisco's western and southern quadrants are dominated by single-family neighborhoods — some of which are well served by mass transit and some of which are not. While there isn't much room left in the city for the kinds of mega-developments like the one still in the works in Parkmerced, there is a ton of opportunity to allow more multi-unit buildings in ersatz-suburban neighborhoods like the Sunset, West Portal, and Glen Park.

SF Supervisor Rafael Mandelman has proposed such an ordinance that will no doubt get pushback from the wealthy denizens of these neighborhoods. As the Chronicle reported in July, Mandelman has asked the city attorney to draft legislation that will make it far easier to build four-plexes on corner lots anywhere in the city that currently have single-family homes on them. And the legislation will also allow four-plexes on lots that are a half-mile away from a major transit stop — such as Glen Park BART.

"I’m a little offended by the idea we care about how many people live in a box of the same size," Mandelman told the Chronicle. "And I’m more offended that we want fewer people living in that box. It’s not sustainable if you want a diverse city."

He's also introducing separate legislation that will make it more difficult to build monstrous "McMansions" on existing single-family lots, as the tech wealthy have been doing in places like Glen Park and Twin Peaks in recent years.

Notoriously progressive San Francisco has long had a history of being notoriously anti-development — with capital-P Progressives wearing their hatred of developers and real estate development as a badge of honor. There is a lot to unpack there, of course, with the pro-redevelopment camp of an earlier generation being responsible for racist "urban renewal" projects in the 1950s and 60s that effectively destroyed the vibrant "Harlem of the West" that was the Fillmore District.

And when the Chronicle's Heather Knight recently praised Sacramento's effort to build more four-plexes, she says this "sparked hissy fits among some supposedly progressive San Franciscans," because these anti-development, anti-change attitudes are alive and well — with gentrification being the assumed intent and consequence of all development that isn't 100% affordable.

Still, there is bound to be more fearmongering and anger, and Mandelman seems prepared for it. He says people have to stop assuming that zoning changes like these are going to mean neighborhoods get mowed down and tenants get pushed out — they simply allow for someone who owns a single-family property to turn that property into four units, but if they want to keep their single-family home they can. None of these changes would likely impact the character of a neighborhood in the next decade or two, or even three.

"Zoning changes are not about the city you have next year or in five years," he said to the Chronicle. "It’s about the city you have in 50 years."

And while racism may not be at the core of San Francisco's extant zoning the way it was in Berkeley, the lack of equity and affordability in the city's housing stock is beyond obvious. One road to fixing that is removing what's keeping suburban neighborhoods feeling so suburban, right within the city limits.

Donald Trump did his fair share of fear-mongering on this topic, talking about how liberals wanted to "destroy the suburbs." But to his racist ilk, they're still talking about the post-war suburbs of the 1950s that were themselves segregationist by design — and for some Trump voters, keeping the white places white is top of mind.

That October 2020 report out of UC Berkeley actually considers San Francisco's percentage of single-family zoning "low" as California cities go, only because we're surrounded on all sides by true suburbs where sometimes 95% of the city is zoned for single-family homes.

But how about we try to be a city? Like, all parts of the city should feel more like a city, not just half of it. A city with fewer cars, and fewer front lawns — even though most of those tiny lawns that used to dot the Sunset have been paved over with concrete anyway.

When those parts of town that used to be sand dunes and became row upon row of middle-class homes were built, this country and this city were very different places.

Like Fran Lebowitz says of New York (though for her this is directed at newcomers and tourists): Pretend it's a city. And let's go from there.