SFist Memoirs is beyond honored to be featuring the magnanimous Pat Montandon this week and next. Fans of San Francisco high society and local history in general are likely already very familiar with Pat and her unlimited arsenal of Bay Area stories, many of which were documented in her memoir, Oh The Hell of It All. The book was a response to her son's memoir, Oh The Glory of It All, which shined quite a bit of undesirable light on his life growing up with Pat and his father, the late Al Wilsey, along with a certain infamous, still prominent member of local high society. But enough about that — when Pat first moved to San Francisco as a young woman, she hit the ground running, quickly earning the endearing title of "San Francisco's Golden Girl." Her stories still resonate with many of us transplants who see a bit of our own experiences in hers.

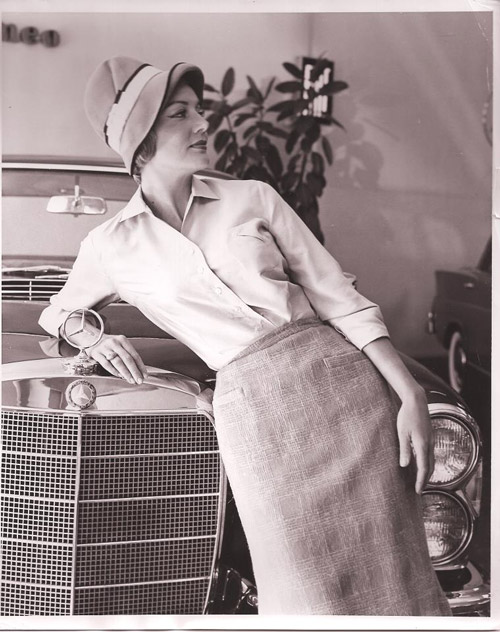

When I first moved to San Francisco in 1960, I was divorced, young, and didn't have a job. I had no money, about $400 to my name. So I got an apartment on the crooked block of Lombard, which was pretty nifty. I had just gotten a job at a clothing store called City of Paris, right downtown in the real heart of the city. Up the block was Joseph Magnin, which was the most successful career-girl store of its kind in the nation — I use the word "career-girl" advisedly now.

I went into Joseph Magnin, thinking, "I'm going to buy something." I couldn't afford it, but I always believed in investing in myself. I've always thought that was the best policy — invest in yourself. I went into Joseph Magnin on a Friday, and I was supposed to start work at City of Paris the following Monday. I got off the elevator and went into their designers salon. There was a woman standing by the elevator when I got off, and I said, "Hello! How are you?" I was just a very friendly person.

She said, "Do I know you?" When I said no, she said, "Well, why are you so friendly?" I thought what a silly question that is. She turned out to be the manager of the department. When I went into the dressing room, she asked if she could come in. She said, "Well, who are you?" I told her, and she said, "You should come work for us." She stayed overtime and took me to a man who I thought was the personnel director. She kept calling him Mr. Cyril. Well, Mr. Cyril was Cyril Magnin, the president of the store.

He interviewed me, and I had no idea what was going on. I was beginning to feel my stuff, you know. I told him I had another job. I went home and got a phone call from the real personnel manager, and she said, "Please, don't go to work at the other store. Come see us on Monday, and I promise you we'll make it worth your while."

So I went in and met with Mr. Cyril again and found out who he was, a major figure in San Francisco. He said, "Miss Cherry" — it's funny that I remember that name — "thinks that you should go to work for us. She thinks you're something."

I looked at him and said, "Mr. Magnin, I am something." I don't know where that came from, but it was due to all that attention I was getting.

He said, "That's good. You got ego. How do you think I got where I got?"

I looked at him and said, "Well, didn't your father own the store?"

So that's how I got my start in San Francisco. I went to work for them, became a store manager in four months and really had a wonderful time. One of the things that was so great was they had such talent working in that store. It was a sink-or-swim situation. Either you could do the job or you couldn't, and they gave you all the room in the world to prove it. One of the people was a fellow named Wally Wood, who they called a window trimmer back then. He was the designer of the windows, and they had gorgeous windows and gorgeous bags. They were known for their shopping bags. People would collect them.

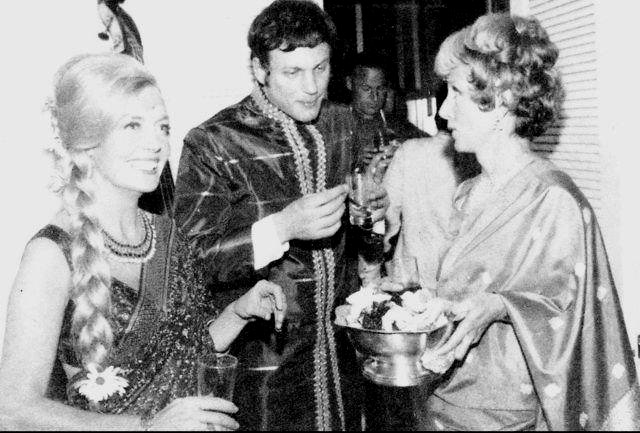

I became friends with Wally, and I was lonesome and started giving parties as a way of meeting people. That was a lesson I learned: I had a passion for parties — it was theater to me, drama, and Wally helped me. That whole department helped me decorate, and other people brought food. I started having these incredible parties. The next thing I knew I was written about in the paper as a socialite. And I was like, "What?!" So funny.

From that, I started doing so many other things. I had a television show, and I became so well known because they were putting my picture in the paper for my parties and anything I did then. I was surprised by it all, but I was reveling in it. It was fun.

The next thing you know, I was taken out to the Haight-Ashbury by a reporter, Gerald Adams, from the San Francisco Examiner — when it was the best paper in town, believe it or not — along with a photographer, during the Summer of Love. All the hippies — there was so much controversy with the hippies. I didn't want anything to do with the hippies, such slovenly characters. Here I was wearing a really delicate white dress, white gloves — we always wore gloves when we went out, cute shoes, and I'm out in the Haight. They stood me up on the street and took my picture, and in back of me is this stoned guy sitting against the storefront smoking a joint. He was so stoned. It was such a contrast with my white dress and white gloves.

The next thing you know, I was taken out to the Haight-Ashbury by a reporter, Gerald Adams, from the San Francisco Examiner — when it was the best paper in town, believe it or not — along with a photographer, during the Summer of Love. All the hippies — there was so much controversy with the hippies. I didn't want anything to do with the hippies, such slovenly characters. Here I was wearing a really delicate white dress, white gloves — we always wore gloves when we went out, cute shoes, and I'm out in the Haight. They stood me up on the street and took my picture, and in back of me is this stoned guy sitting against the storefront smoking a joint. He was so stoned. It was such a contrast with my white dress and white gloves.

Then Gerald started asking me questions. He was really leading me on because I was pretty innocent about it all. I wasn't quite as savvy about the press as I later became. He said, "What do you think about the hippies?" And I said I'd never want to be a hippie.

Then he asked, "What do you think about the topless girls?" At that time topless had become really big in North Beach.

I said, "Oh my goodness," or something erudite like that.

He asked, "Do you think they're beneath contempt?"

I said, "Oh yes, beneath contempt." He was really feeding me my lines, and I ate them up.

The next day, the paper came out with a big picture and story, and suddenly I heard noise. I look out my window — I was right on the crooked block of Lombard, I looked down, and there were the topless girls with their signs. They were making the most of the story. They were wearing fur coats over their toplessness and carrying picket signs, picketing me: "Pat Montandon doesn't know what she's talking about." That kind of thing. It was so funny.

I didn't know what to do. I wasn't going to go out my door. I called a friend, and he said, "Don't ask me. You got yourself into this." The press came out. There were television cameras because the topless girls, or their bosses, notified the press.

So a friend of mine came over who worked at KCBS. I have an entry way, and then my front door. I opened my door, went out to open the other door, and a gust of wind came in and slammed my door shut. I couldn't get back into my house. It turned out to be a comedy of errors. He smuggled me out and took me to his house. His wife made me a peanut butter sandwich, and we laughed together over the whole thing.

That was such a funny time. I was young and fun and having fun with it all, but I would get myself into these predicaments without realizing it.

Read more of Pat's stories next week. Pat has a new book coming out soon, titled, Peeing on Hot Coals, a memoir about her early childhood. Be sure to "like" her on Facebook!

--

You — yes, you! — have some Bay Area stories. Tell them to us: [email protected]!